The Divine Connection of BharatNatyam & Yoga

NrityaChuramani Rahul Dev Mondal ( Assistant Professor , Rabindra Bharati University , Department Of Dance )

In the Hindu tradition, gods and goddesses dance as a way of expressing the dynamic energy of life. The image of Nataraja represents the god of gods, Shiva, as the Lord of the Dance, choreographing the eternal dance of the universe as well as more earthly forms such as Indian classical dance (which is said to have originated from his teachings). In Hindu mythology Shiva is also Yogiraj, the consummate yogi, who is said to have created more than 840,000 asanas, among them the hatha yoga poses we do today. While a cultural outsider may not relate to these mythic dimensions in a literal way, dancers in India revere the divine origins of their dances, which were revealed to the sage Bharata and transcribed by him into the classic text on dance drama, the Natya Shastra (circa 200 c.e.). What many practitioners of yoga do not know is that one of the central texts of yoga, Patanjali’sYoga Sutra, written around the same time, was also inspired by an encounter with Nataraja.

My Body as Temple, Dance As Offering

The first movement I learned from my BharatNatyam master dance teacher, was Bhumi Pranam. Just as Surya Namaskar (Sun Salutation) honors the sun, this movement honors (the translation of pranam is “to bow before or make an offering to”) bhumi, the Earth. Bhumi Pranam is done before and after every practice and every performance. With hands together in Anjali Mudra, I was taught to bring my hands above my crown, to my forehead (Ajna Chakra), the center of my heart, and then, with a deep opening through the hips, to touch the earth. Bhumi Pranam expresses the essence of dance as a sacred offering that recalls B. K. S. Iyengar’s famous saying, “The body is my temple and asanas are my prayers.”

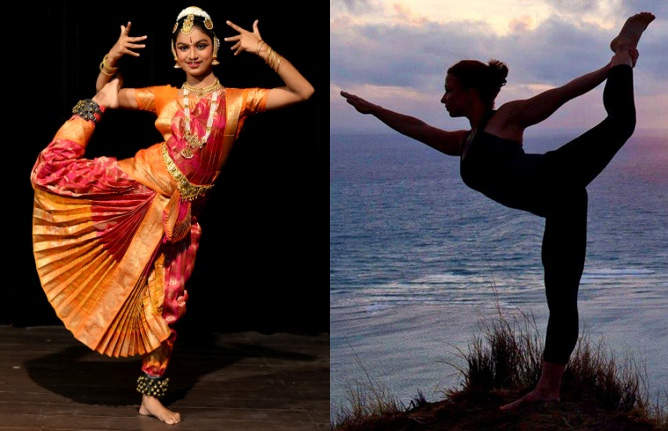

In this case, dance is the offering; indeed, in classical forms such as Bharatha Natayam , the dance actually originated in temple complexes, where 108 karanas were sculpted into the walls of temple entryways. These detailed reliefs reflect the traditional prominence of temple dancers known as devadasis (“servants of God”), who are thought to have incorporated some elements of yoga practice into their art.

There are only a few living devadasis left, and Bharata Natyam is usually done in a way that emphasizes entertainment (while still demonstrating a depth of devotion rarely seen on the stage). The text of Natya Shastra unites the various forms of Indian classical dance by means of a ritual performance format that is still followed (with some variations among different styles). Many forms begin with an invocation to the Divine, or pushpanjali (“offering through flowers”), to root the dance in sacred expression. A pure dance section called nritta follows, showing with great skill the movement vocabulary of the form and the union of the dancer with tala (rhythm). The heart of a dance performance involves abhinaya, a combination of dance and mime in which a dancer or dancers will embody characters of a sacred story cycle by expressing the lyrics and rhythm of accompanying songs through body language, hand mudras, and facial gestures. The songs are based on mythic stories such as the Shiva Purana, Gita Govinda, or Srimad Bhagavatam.

The Balance of the Sun and Moon

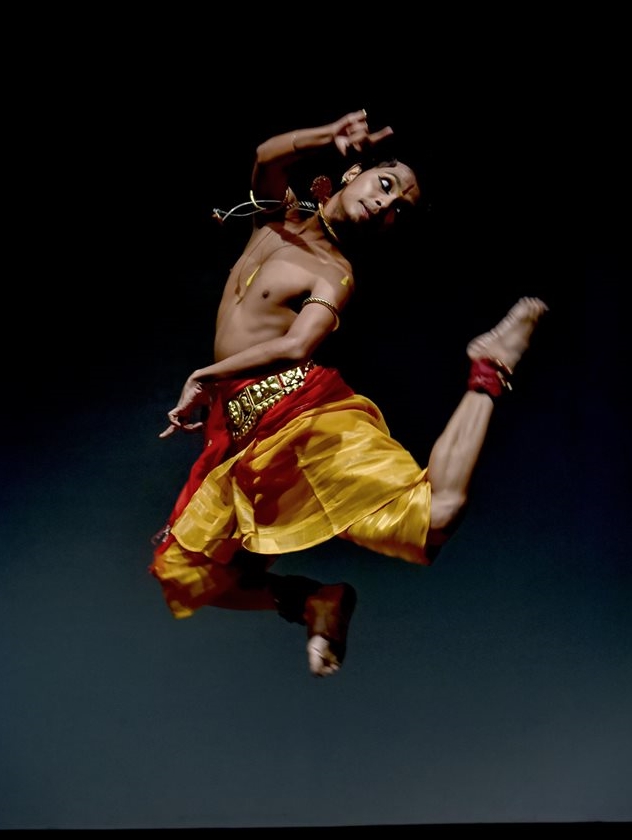

While there are many philosophical and practical connections between yoga and dance, the principle of unifying opposites is essential to both systems. Practitioners of hatha yoga are often told that the word “hatha” represents the figurative joining of the sun (ha) and the moon (tha), respectively masculine and feminine energies. On a practical level, this often translates as the balance of differing qualities within a pose: strength and flexibility, inner relaxation and focus. Within Indian classical dance forms, this balance of the masculine and feminine is understood as the balance of tandava and lasya. Tandava is associated with strong, vigorous movements and is considered to be the vibrant dance of the virile Shiva. Its complement, lasya, the dance of Shiva’s consort Parvati, embodies graceful, fluid movements. Dances are often classified as being tandava or lasya in the same way that certain asanas or Pranayamas are classified as heat-generating or cooling. In BharataNatyam , tandava and lasya become embodied within the structure of the karanas, with tandava being the lower body and lasya the upper body. Tandava is the strong stamping of the feet, like Shiva, and lasya is the fluidity in the torso and the grace of the hand movement or mudras.

In Kuchipudi dance, a solo dancer can embody the two qualities in the form of Shiva Ardhanarishvara whose visage is half male (Shiva) and half female (Parvati). In costume, the dancer will dress differently on the two sides of the body and will perform the characters of both parts by showing one side or the other.

From Alignment to Mastery

Another area where dance and hatha yoga meet is in the actual sadhana (practice), where there are many parallels between the two arts in both the technique and spirit (bhava) of the dance. The tradition is passed from guru to shishya (student) in a live transmission; the teacher gives the proper adjustments and guides the students into the inner arts of the practice. All of Indian classical dance refers back to the Natya Shastra text for an elaborate classification of the form. If you thought the technique of asana was detailed, you should peruse the Natya Shastra: It not only describes all the movements of the major limbs (angas)—the head, chest, sides, hips, hands, and feet—but also offers a detailed description of the actions of the minor limbs (upangas)—including intricate movements of the eyebrows, eyeballs, eyelids, chin, and even the nose—to create specific moods and effects. As in hatha yoga, one begins with the basics of body mechanics and gradually moves toward the subtler aspects of the art.

The karanas, dance counterparts of asanas, are linked into a sequence known as angaharas. The dance forms emphasize staying grounded, relating all of the movements with gravity to the earth, then reaching to the heavens. The emphasis on stilling the mind through concentration on the inner and outer bodies, moving the practitioner toward an experience of freedom, also parallels the inner processes of yoga. When I was first learning the basic steps of BharatNatyam , it took all of my concentration to keep a strong and consistent rhythm with my feet while tilting my head and eyes in opposition to my torso. I felt very mechanical and awkward, just like many beginning students of yoga. Only through repetition and focus on precision did I start to feel a flow of grace, or lasya. Watching the more experienced dancers practice and perform gave me a deep respect for the mastery that is the eventual fruit of so much sadhana.

Studying BharatNatyam gave me enough patience with my Ashtanga Yoga practice to allow me both to embrace technique and to let go. Both processes can lead to a state of embodied communion. Ultimately, yoga is about connecting to the Big Dance, which one can experience either abstractly, through the lens of spiritual culture, or more intimately, as did physicist Fritz of Capra. In his book The Tao of Physics, he describes the experience he had while he was sitting on the beach and watching the waves, observing the interdependent choreography of life: “I ‘saw’ cascades of energy coming down . . . in which particles were created and destroyed. I ‘saw’ the atoms of the elements and those of my body participating in this cosmic dance of energy. I felt its rhythm and ‘heard’ its sound and at that moment I knew that this was the Dance of Shiva.”

References:

- Kothari Sunil – BharatNatyam – Indian Classical Dance Art, Marg

- Sastri Gourinath – Abhinaya Darpan

- Das Nilmoni – Byam O Sastho – Iron Man Publishing House

- Vivekananda Swami – Patanjali Yoga Sutra – Vijay Goel( Publisher)

*************************************************************************