Features for Style Identification of Hindustani Musicians

Dr. Kaushik Banerjee, Dr. Anirban Patranabis, Dr. Ranjan Sengupta, Dr. Dipak Ghosh

Sir C V Raman Centre for Physics and Music, Jadavpur University, Kolkata 700032

Abstract

Identification of style of a musician is hard to recognize by an amateur listener, but to expert music listeners or to the musical ears just one or two strokes are enough to recognize. So, what are the physical causes behind this mystery? Our aim is to find out those causes and analyze in such a way that could satisfy the musical standpoints. Important elements from the physical perspective are steady states of notes and silence. Steady states of note recognize prominent presence of a note. Number of occurrence of a note in a signal articulates the importance of that note. Use of silence is also a style statement of a good musician and it varies from one musician to another. There are some unique musical ornaments like Meend which is exclusively use in Indian music. Measure of silence, steady states and meend are good parameters for style analysis.

Introduction

A music genre is a conventional category that identifies some pieces of music as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions. It is to be distinguished from musical form and musical style, although in practice these terms are sometimes used interchangeably. An artistic form of auditory communication incorporating instrumental or vocal tones in a structured and continuous manner is expressive style.

Ustads used to be very orthodox in general but there were few exceptional personalities like: Ustad Wazir khan, a descendent of Mian Tansen through daughter’s lineage (Senia Binkar Gharana) (B K Roy Chowdhury, 1974). He taught Ustad Allauddin Khan, founder of Senia Maihar Gharan and one of the legendary musicians of 20th century. Along with Wazir Khan, Allauddin Khan also learnt from about ten more gurus (teachers) (K Banerjee, 2007).

As a result, he had a huge musical knowledge over different musical instruments and Gharanas. At the same time, he was much liberal in all respect of his contemporary musical legends. His authority and authenticity of knowledge over different musical instruments reflected on his disciples (Pt J Bhattacharjee, 1999). Some of them were would be legends of the next century. We include two of them in our study; one is Pandit Ravi Shankar and the other is Pandit Nikhil Banerjee. Noticeably, both of them were Sitar player from Senia Maihar Gharana but their playing styles were different.

Sahabdad Khan, a great exponent of Sarengi and also played sitar and surbahar of 19th century. He used to stay at Etawah from which his Gharana has been known as Etawah Gharana. Sahabdad’s son Imdad khan was born in Etawah, later he went to Indore where he got talim from great binkar Ustad Bande Ali Khan (H K Roy Chowdhury, 1929). His rigorous practice and fast Gat-tora playing in sitar is still hearsay to the musicians. He was one of the greatest sitar and surbahar players of his time. His unique style of sitar and surbahar playing made him legend and since him Etawah Gharana is also known as Imdadkhani Gharana. He used to play Alap-jore and Jhala on surbahar followed by Gat–tora on sitar (S Bhattacharya, 1999). This style was also maintained by his able son Ustad Inayet Khan (H K Roy Chowdhury, 1929).

Among his two sons Vilayet Hussein Khan was elder. When he was born Inayet Khan was court musician of Gouripur of Mymensingh, East Bengal (now Bangladesh). Due to Inayet Khan’s premature death, Vilayet Khan’s musical talim was mostly from his uncle Wahid Khan and maternal grandfather Bande Hassan Khan (K Banerjee, 2007). He also acknowledged the influence of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan (K Banerjee, 2007). Hence, his style of playing was a little bit different. Though he used to play both surbahar and sitar but he started his career as a sitar player and as a representative of Etawah or Imdadkhani Gharana.

It is fact that changing political situation transforms the entire socio-economic condition, or better to say, total ambience of a country, and this was happened to Indian subcontinent during early to mid of 20th century. It was a Juncture to India in all respect. However, through the musical perspective, it was really a crucial period. Raja-maharajas lost their power, Zamindari system was also abolishing. Ultimately, musicians, especially great musical legends were in perplexed conditions. Once, they have to only satisfy the king and his courtiers who were mostly connoisseur of music. And in exchange of that, they used to get secured and luxurious life as per their excellence and family background. Now, they have to please the common people with a different musical sense. Like this ambiance and time, Ravi Shankar, Vilayet Khan and later Nikhil Banerjee started their musical career (K Banerjee, 2007) and within few years they have become the most famous sitar players and faces of India to the world. So, these are the cause to choose three legends music for our current experiment.

Thus, here style refers to individual identity, excellence, along with presence of all characteristics of Gharana which expressed through playing of same music (raga) on the same musical instrument. It was observed that, at the time of rendition all of them depending on few musical ornaments which convey their attitude best. For that reason, while one artist depending on meend, gamakas, other on deferent variation and fraction of laye (tempo), krintan, jamjama, and remaining artist on meend, fast tans etc.

Previous works on style analysis are mostly on western music like: classification of Western music genres using melodic features computed from pitch contours (J.Salamon et al.2012). Jan LaRue (1981) attempted to classify audio signals according to their cultural styles by using characteristics like timbre, rhythm and musicology-based features. These research papers either classify western musical genre or are based on categorization of sound, melody, harmony, rhythm to recognize composers in conceptual patterns etc. In the domain of Hindustani music there are very few works have been reported. Datta A.K. et.al. (2017) have done some computational analysis for automatic recognition of raga. Vidwans A et.al (2012) have detected Indian classical vocal styles from melodic contours. Feature based computational approach for style identification in Hindustani music is scarce. Present study identifies the style and the similarity and differences in the music of three maestros.

Experiment

Three raga renderings in raga ‘Bhairavi’, ‘Darbari’ and ‘Kafi’ played in Sitar by renowned artists like Nikhil Banerjee, Ravi Shankar and Vilayat Khan was collected from different archives. Thus a database consists of nine signals each of one minute durations was formed. Each raga has some common phrases. All the signals were digitized at a sampling rate of 44100Hz (16 bits per sample) in mono channel. From each signal, detection of the tonic ‘Sa’ position, extraction of other notes (with pitch value) and pitch profile and other respective and essential procedures regarding this experiment were done as per our previous research works (Banerjee. K et. al. 2012, Datta A. K et al 2006, Datta A.K et al 2009).Following are the key features which identifies the style of playing of anartist’s: (a) frequency of uses of each notes – compared for all raga renderings for all notes used. This reflects the preferences of using touching notes and long notes. (b) Duration of notes – compared for all raga renderings for all notes used. In some rendering we found a very strong preference for a single note while in other an equal weightage was given to two or more notes. (c) Duration of silence – reflects the tempo and artist’s mood during the performance. (d) Total number of steady states and total duration of steady states and (e) Duration of transition between notes – unveiled the artist’s mood. In Indian classical music, transition between notes is one of the most important features of expertise and renowned artists’ love using transition notes. (Datta et al, 2017). Although timbre is an important characteristic in distinguishing sound signals we have emphasized on musicological perspectives only.

Results

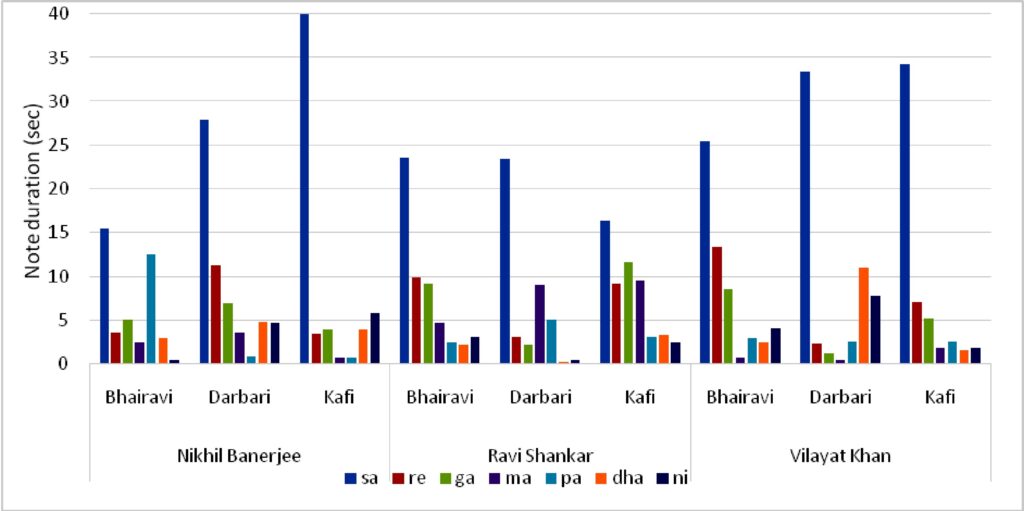

Figure 1: Note duration in second for three ragas and for three artists

Steady states of note recognize prominent presence of a note. Number of occurrence of a note in a signal articulates the importance of that note. And in this way we can get Vadi, Sambadi, Anuvadiand Barjit notes. Specific notes associated with each stroke made on the main strings as well as the sympathetic and chikari strings were taken into consideration. From figure 1 it is observed that due to the presence of sympathetic and chikari string vibration, the note ‘sa’ is the most dominant note and this is one of the important sound characteristics of Indian plucked Musical Instruments with sympathetic strings like sitar. Although the phrases of the three ragas remain same, it is observed that the notes played by the three maestros are totally dissimilar from each other. Unlike western music there is no fixed rule of using notes in Hindustani music (HM) but fixed combinations of note exist for a given raga. In HM, other than Chalan (ascending-descending movement of notes in such a way which is specific for each raga) and Pakad (minimum combination of notes that exactly convey a particular raga), there is no fixed rule like western music. Artists played the notes of their own style keeping the phrasal pattern and mood of the raga constant. Thus artists improvise their performances with various combinations of notes.

Figure 2: Ratio of average silence duration to note duration

Silence is like colours of the canvas upon which music is painted. Proper utilisation of silence in HM is one of the key factors that affect the listener. Without silence the music would be mere noise to the listeners. In Hindusthani music, a good musician learns from his/her guru how to take intervals in making notes prominent (Vadi, Samvadi etc.) or in between Tan/Tora etc. Later, at the time of rendition, conscious practice goes in their subconscious mind and they do it very naturally. Amazingly, the use of silence is also a style statement of a good musician and it varies from one musician to another. So, measure of silence is a good parameter for style analysis. So the coherence of notes and silence is very important in HM. Therefore, the length of silence and the ratio of silence duration to the note duration are important features to identify the style of an artist. We have measured all the silence and note durations for all the signals. Then we measured the ratio of the average of silence and note durations and are shown in figure 2. The figure is self-explanatory and clearly distinguishes the style of the three artists. A low value of silence to note ratio indicates a less silence duration while larger silence to note ratio indicates longer silence duration. In all the three renderings of Ravi Shankar larger silence to note duration is found and hence silence zones are dominating in his renderings. Average note duration and number of notes played by Ravi Shankar is less than the other two artists. He also played more short durational notes than long durational notes. In all the renderings of both Nikhil Banerjee and Vilayat Khan a smaller value of silence to note duration is found. A minute observation indicates a larger silence duration for Nikhil Banerjees’s renderings than compare to Vilayat Khan’s rendering. But a very little difference in average note duration is observed among the two artists. But again a minute observation indicates that Vilayat Khan played much more long durational notes than Nikhil Banerjee in all the three renderings. Hence we may conclude as that Ravi Shankar’s style includes longer silence duration but smaller note duration with more number of notes, while Vilayat Khan’s style includes smaller silence duration with long durational notes. In comparison with the two artists Nikhil Banerjee’s style is in between the two. So these two features are very important cue to distinguish style of musicians.

Figure 3: Scatter plot of total number of steady states

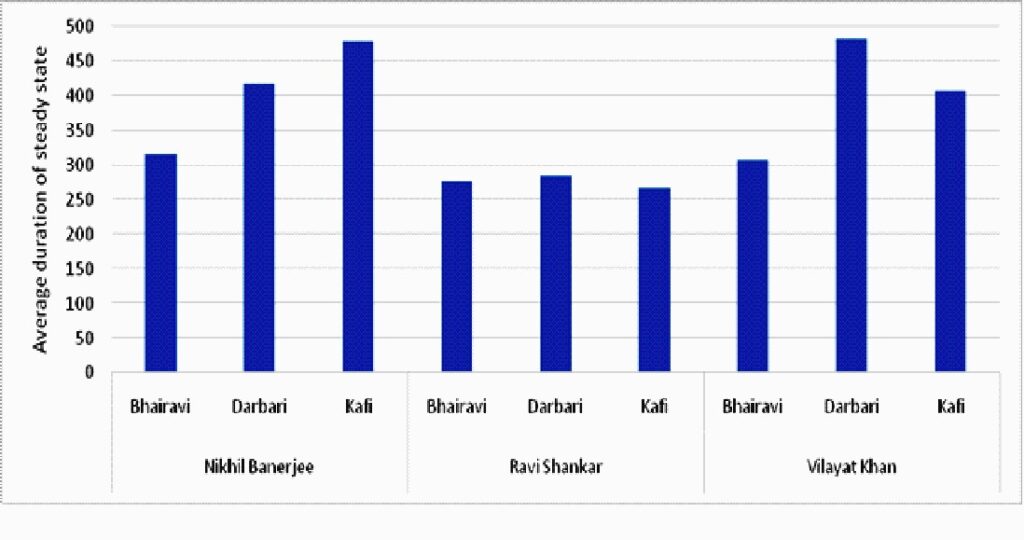

We also measure the steady states of the sound signals of the main strings only. We considered a note duration greater than 100 ms as a steady state. We have measured number of such steady states and also the total duration of steady states. Scatter plots of total number of such steady states are shown in figure 3 and a bar diagram of average duration of steady states for all the ragas is shown in figure 4. A lowest number of steady states are observed in the renderings of Nikhil Banerjee but his style of music includes very long durational steady state notes. In comparison with the other two artists he played least number of long durational notes but longest stead state duration. Although Vilayat Khan played long durational steady state notes, he played lesser number of steady state notes. Ravi Shankar’s style of music shows a highest number of steady state notes but average duration of steady states is smallest in comparison with the other two artists. Hence figure 3 and 4 clearly distinguish the style of three artists. In general, Ravi Shankar played frequent but shorter durational note while both Nikhil Banerjee and Vilayat Khan are comfortable with long durational note. It is also observed that the average steady state durations of raga Bhairavi is almost similar for all the three artists but for the other two ragas no such similarity is observed.

Figure 4: Average duration in millisecond of steady states for three ragas and for three maestros

Figure 5: Total meend (transition between notes) duration

Another important feature for style analysis is the transition between notes. Transition between two notes with a sliding tone is known as Meend in Indian classical music. It is an essential and integral part of Indian classical music that gives the essence of Indian classical music which is strictly prohibited in western music (Datta et. al, 2009). Pitch transition and note sequence are significant to the listeners in identifying the melodic similarity (Datta et. al, 2009). We had identified the transition area between notes used by the artist and measured the total transition time for the whole signal. Figure 5 shows the total transition time for all the nine signals. It is observed that Ravi Shankar played shorter meend in all the three ragas. But no such consistency is observed for the other two artists. Nikhil Banerjee played shorter meend in raga Bhairavi and Kafi but he played longer meend in raga Darbari. Vilayat Khan played longer meend in Bhairavi and Darbari but he played shorter meend in Kafi. Utilisation of gliding notes is different for individual artists. For the raga kafi all the three artists played the gliding notes almost with equal transition time. For raga Bhairavi Nikhil Banerjee and Ravi Shankar both played the gliding notes with equal transition time but Vilayat Khan used much longer transition time in the said raga. All the three artists played the meend differently in raga Darbari. So Ravi Shankar’s style of music can be identified illicitly by the parameter transition time between gliding notes.

Conclusion

Due to the presence of sympathetic and chikari string vibration, the note ‘sa’ is the most dominant note and this is one of the important sound characteristics of Indian plucked Musical Instruments with sympathetic strings like sitar.

The length of silence is an important measure of style recognition. Also the ratio of silence duration to the note duration is important features to identify the style of an artist.

Each artist has different tendency of playing steady notes and steady state duration is unique for an artist.

Transition time between successive notes is different for different artists. Preferences of using number of notes during meend production are also unique for an artist.

This study helps the amateur learners to follow the styles of successful and famous artists.

References

Banerjee.K, Patranabis. A, Sengupta, R and Ghosh. D (2012), “Search for spectral cues of emotion in Hindustani music”, Proceedings of the National Symposium on Acoustics-2012 (NSA-2012), 5-7 December, KSR Institute for Engineering and Technology, KSR Kalvi Nagar, Tiruchengode – 637215, Tamilnadu.

Banerjee Kaushik (2007), “Bharatiya Sangeeter Bikash O Antarjatikikarane Ustad Allauddin Khan Ebong Tar Uttarsurider Aabodan (Bengali)”, Thesis paper (unpublished) Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata.

Banerjee Kaushik (2017), Indian String Musical Instruments –Making &Makers, Parul Prokashani Pvt. Ltd., 1st edition, . ISBN 978-93-86186-61-4. KOLKATA, 2017

Datta A K, Sengupta R and Dey N (2009), ―’Objective Categorisation of Meends from Hindustani vocal performances’, J Acoust. Soc. India, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 92-95.

Datta A K, Sengupta R, Dey N and Mukherjee A K (2006). ―’A methodology of note extraction from the song signals’, Proc. Int. Symposium- Frontiers of Research on Speech and Music, U P Technical University, Lucknow, India.

Datta A K, Sengupta R, Dey N and Nag D (2006); “Experimental Analysis of shrutis from performances in Hindustani music”, Monograph published by ITC Sangeet Research Academy, Kolkata, ISBN 81-903818-0-6.

Datta A K, Sholanki S S, Sengupta R, Chakraborty S, Mahto K and Patranabis. A et. al. (2017), “Signal Analysis of Hindustani Classical Music” Pub- Springer, 2017, ISSN 1860-4862, ISBN 978-981-10-3958-1.

Ghosh Laxmi Narayan (1975), Geet – Baddyam:, Pub: Pratap Narayan Ghosh, 1st edition, Calcutta 1975.

Liu Y, Xiang Q, Wang Y and Cai L (2009), “Cultural Style Based Music Classification of Audio Signals,” Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing.

Miner Allyn (1997), Sitar and Sarod in the 18th and 19th Centuries, published by – Motilal Banarsidass Publishers PVT. LTD, First Edition 1997, Delhi.

Pandit Ravi Shankar (1999), Rag-Anurag, edited by Shankarlal Bhattacharya, Ananda publishers, 1st edition, 3rd print, Calcutta (1999).

Pandit Bhattacharjee Jotin (1999), Ustad Allauddin Khan O Aamra (vol- II), Pub- Amit Bhattacharjee, 1st edition, January 1999, Calcutta.

Roy Chowdhury Harendra Kishore (1929), The Musicians of India (illustrated) Part-1(reprint), Kuntalin Press (1929), Calcutta.

Roy Choudhury Bimala Kanta (1974), Bharatiya Sangeet Kosa, Calcutta, Kalika press.

Salamon J, Rocha B and Gomez E (2012): “Musical Genre Classification using Melody Features extracted from polyphonic music signals”, IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing.

Vidwans A, Ganguli K K and Rao P (2012), Classification Of Indian Classical Vocal Styles From Melodic Contours, Proc. of 2nd CompMusic Workshop, Istanbul, Turkey, 12-13, July.