Dances in Bangladesh- Joysree Biswas

Joysree Biswas, Ph.D. Scholar, Dance (ICCR Research Scholar ) Research Supervisor Dr. Ami Pandya, Department of Dance, Faculty of Performing Arts, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Gujarat

Abstract

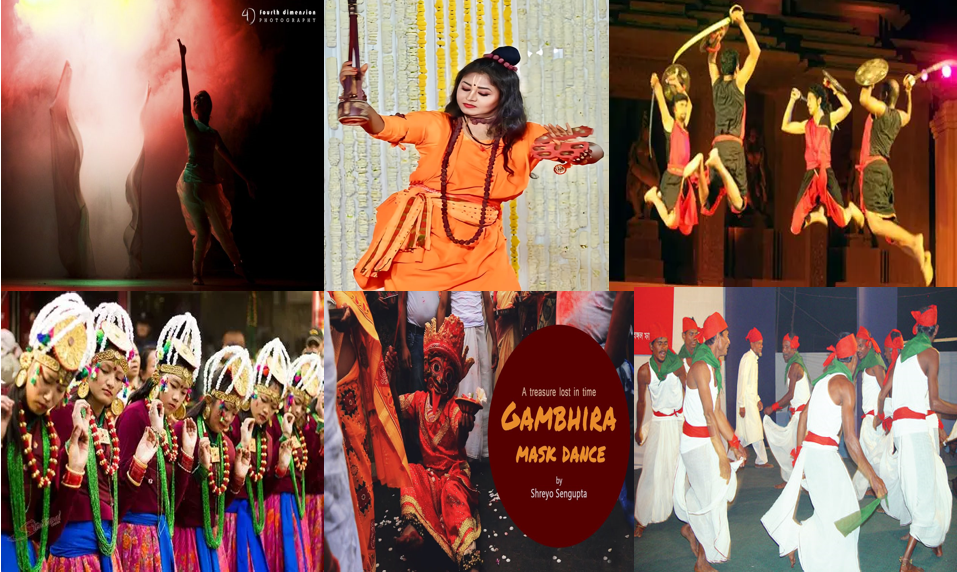

Dance in Bangladesh encompasses a rich tapestry of forms, primarily categorized into folk and classical styles. Folk dance, the most prevalent, is characterized by its simplicity and spontaneity, allowing for personal expression while adhering to traditional structures. Various folk dances, such as Dhamail, Baul, Dhali, Gambhira, Ghatu, Jari, and Khemta, reflect the diverse cultural and religious influences of the region, often performed during community celebrations and rituals. Classical dances, including Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Odissi, and Manipuri, though originating from India, have found a place in Bangladeshi culture. Additionally, tribal dances showcase the unique traditions of various ethnic groups, while contemporary styles like hip-hop and salsa are gaining popularity. Overall, dance in Bangladesh serves as a vital medium for cultural expression, storytelling, and community bonding.

The act of moving one’s body parts in rhythm with music and with appropriate expression is known as dance. The primary type of dance practiced in Bangladesh today is folk dance, which is also known as Bangladeshi regional dance. Among eight classical dance forms, just four forms, including Kathak, Bharatanatyam, Odissi, and Manipuri, are widely performed in Bangladesh, with the exception of folk dance. The eight traditional forms are as follows: Bharatanatyam from Tamil Nadu. Kathak from the western and northern regions of India. Kerala has Kathakali. Kuchipudi from Andhra Pradesh. Odissi from Odisha. Manipuri dance from Manipur. Kerala’s Mohiniyattam, Assamese Sattriya

Different kinds of Classical Dance art forms in Bangladesh

The emphasis of the abstract, quick, and rhythmic Nritta performance is on its movement, shape, pace, range, and pattern. It is regarded as a technical aspect of the performance and includes no interpretation or narrative. Although these classical dances originated in India, they are now part of Bangladesh’s cultural heritage and are not considered a part of the country’s national identity.

Dance of the People in Bangladesh:

Folk dance, which originates from several regions of Bangladesh, is our primary dance when we talk about dance in the nation. Compared to classical dance, folk dance is simpler and more spontaneous, making it easier to learn. However, a lot of practice is necessary to master classical dance.

From one generation to the next, folk dance has been handed down. Folk dance gives artists the freedom to express themselves while maintaining the fundamental structure as a matter of custom.

Folklore dance may be performed alone or in a group. The majority of group dances take place in Bangladesh.

In Bangladesh, there are many different dance forms, including tribal, fakir, bede, jele, khemta, ghatu, chhorra, lathi, jari, gambhira, baul, and damail.

In most Asian nations, folk dances are primarily divided into three categories: nonsecular, social, and cultural.

Dances with a non-secular focus include alternative forms. Dances about Muslim rites, Baul rites, kirtan, penance, Gambhira, and Jari are all connected to very different religious convictions and rituals. The martial arts are linked to the Dhali and Lathi dance squares, while the chakras, Ghatu, and Khemta dances provide amusement.

Some dances are influenced by Islamic ideas and tales, while others are influenced by Hindu mythology and folklore. The majority of the audience and participants in these dances come from their various communities. But certain dances have universal appeal.

For example, the Muslim community mostly enjoys the Jari dance, while the Hindu community primarily enjoys the kirtan dance. The lathe or Dhali dances square measure enjoyed by all, whereas the chakras, Ghatu, and Greco-Roman deity dances are mainly supported by the Muslim community, but their performances are appreciated by all other communities.

Dhamail Dance

Dhamail, a variation of Dhamal, is a dance form that may have its roots in Sylhet, Bangladesh, and may also be a type of mainstream music.

The Asian nation practices it in the former Sylhet district as well as in regions that have been impacted by the Sylheti culture, such as Cachar, portions of the Karimganj and Hailakandi districts of Assam, and portions of Tripura. It goes along with the usage of the mridanga, kartals, and a variety of additional musical instruments, some of which are played by the men during the dance.

This dance style is akin to musical chairs, where the dancers are progressively squared off by the dancers who will dance in no time since the beats establish the pace. This dance style primarily emphasizes the love between Radha and Krishna, and its core meaning is that the newlyweds should join their hearts in this way.

The womenfolk are the primary performers of the song and dance during marriages and other auspicious occasions. The women clap their hands to the beat of the music while moving in a circle. The leader first sings the songs square measure so that the others can join the chorus. The majority of the words are about Shyam (Krishna) and Radha.

The Baul dance

The nonsecular rituals of Bauls include Baul dance. Baul songs have a nonsecular theme, and during these tunes, Bauls eventually fall into a state of bliss and start dancing. They are holding associate ektara in their hands. Some people wear Ghungur, a string of bells, around their ankles. People sometimes do square measure Baul dances, but they also do group or duet dances at their Akhda occasionally.

There are no prescribed movements in the Bauls’ performance arts, which include swaying their heads and hair, twisting, and moving their arms and legs. The ektara, which is often held high and near the ears, has an amazing role in the dance. The Kushtia and Jessore districts of Asian nation, as well as the Burdwan and Birbhum districts of West Bengal, are the main centers for this dance.

The Dhali dance

A duel is depicted in the dhali dance (literally, defend dance) between two guys whose weapons are bamboo sticks and heavily plain-woven cane shields. The supporting cast consists of drums and brass cymbals. The primary goal of this dance is to highlight the performers’ physical prowess and martial abilities.

In the beginning, the two warriors face each other menacingly, in time with the music, before launching their attacks and counterattacks while standing or moving. The simulated conflict lasts until it reaches its conclusion. People fair in the Khulna and Jessore regions sometimes feature the Dhali dance.

In a literal sense, the Dhali dance is a duel between two men using bamboo sticks and cane shields with a thick, plain weave as their weapons. The support is provided by brass cymbals and drums.

In its most objective sense, this dance demonstrates the dancers’ physical prowess and martial abilities. The two warriors begin by facing each other aggressively and in time with the music before executing their offensive and defensive strikes, either on their feet or on the move. This fake war continues until it reaches a conclusion. The Dhali dance is occasionally performed at fairs in the Jessore and Khulna area.

The dance of the Fakir On the occasion of his Ur’s, the followers of Madar Pir perform this dance. At the top of Chaitra (March-April), at the Pir’s tomb, hairy devotees dressed in long, loose attire burn candles and incense.

The Pir’s likeness is represented by a bamboo covered in red and topped by a fly-whisk. Others follow one supporter who is carrying the bamboo on his shoulder. They have bells that are round around their ankles. The Pir is provided for by burning meat on a lit fireplace. The practitioner dances around the hearth while swinging their head to the rhythm of the music.

https://pt.pinterest.com/pin/173388654393022436/

Gambira Dance

Serious dance in the formerly undivided geographic region, this dance used to be popular in the Maldah region, where it is performed with Gambhira songs. It is still performed in Rajshahi, albeit not as well as it once was.

A try of performers performs the dance, with one of them playing the part of a nana (maternal grandfather) and thus distinct from his Nati (grandson). They address contemporary social, political, economic, and moral concerns through their salvation and singing. The conversation is both in prose and poetry. The song’s refrain is repeated by a chorus.

The reed organ, flute, drum, and Judi are the most melodic supporting instruments. Folk’s play is similar to the Gambhir dance, which includes a combination of conversation, dance, songs, and music. The nana and Nati dance, with the Nati wearing a string of bells around his ankles, while the choir sings the refrain. The artists of Maldah wear masks.

The Ghatu Dance

The dance of Ghatu, the Ghatu melodies are accompanied by this dance. It aims to amuse the audience completely, without any social or non-secular subject. Its main draw is one or more adolescent guys dressed as women. Sometimes, the tale of Radha and Krishna has been backed by the lyrics. One person sings while the others dance.

Fashionable love stories also back up dances. The flute, drums, cymbals, and thus the sarinda are the most musical instruments. Nowadays, the reed organ is also used. The dance continues for many hours throughout the night. Sometimes the dance gets too obscene, which is why Ghatu sessions are occasionally held outside of populated areas.

The Ghatu Dance This dance is performed to Ghatu songs. Its only purpose is to amuse the audience; it has no religious or social themes. Its primary draw is one or more adolescent males dressed as women. Sometimes the tale of Radha and Krishna has been supported by the songs. The others are dancing as one person is singing.

Popular love stories also back up dances. The most melodic instruments are the flute, the drum, the cymbals, and hence the sarinda. The reed organ has recently been added to the list. The dancing continues throughout the night, sometimes becoming rather obscene, which is why Ghatu sessions are occasionally ordered outside populated areas.

The dance of Ghatu. This dance is performed in conjunction with Ghatu songs, which are purely for the purpose of amusing the audience and have no religious or social themes. One or more adolescent males disguised as women are its main draw. The story of Radha and Krishna has occasionally been supported by the music. While some people dance, one person sings. Popular love stories are another way that dances are supported.

The most musical instruments are the drum, cymbals, the flute, and thus the sarinda. In recent years, the reed organ has also been employed. The dance lasts for many hours throughout the night. Occasionally, the dance becomes somewhat vulgar, which is why Ghatu sessions are occasionally ordered outside of populated areas.

The Kishoribhajan, a Vaishnava sub-sect, features young women singing bhajans and dancing. The Kishoribhajan may have had an impact on the narrative of Radha and Krishna, as well as on Ghatu songs and dances. Recently, the popular Ghatu dances have been performed on trendy stages in Kishoreganj and Netrokona.

Jari & Gambhira dance

Jari dance This dance, which is occasionally performed by Shiite Muslims, goes along with jari singing. It is held throughout Muharrum and tells the tale of Imam Hossain’s tragic demise at Kerbela. A jari dance cluster is made up of around 8–10 young people. The others are called Dohar because the head of the group is known as Ustad. Although the dancers dress in regular attire, they also tiered handkerchiefs around their wrists and browse.

In some places, they wear strings of bells tied together around their ankles. In general, the Dohars maintain the beat and carry on the rhythm by playing the Jharni, which is made of bamboo, while the Ustad plays the Chati. The beat is maintained by approval in certain areas. The Ustad sings from the middle. The Dohars surround him in a large circle, repeating the chorus of the tune. The dancers express their anguish by the motions of their heads, hands, and feet.

The Muharrum moon is watched before any jari dance performances. Jari teams visit a wide variety of residences in the community. In exchange for their performances, they are compensated with money or food. The various dance groups gather at the chosen location of Kerbela for one last performance on Ashura.

The dance of Jari This dance, which is sometimes performed by Shiite Muslims, is performed alongside jari singing. It is held all throughout Muharrum and depicts the sad passing of Imam Hossain in Kerbela. A jari dance cluster is made up of around 8-10 young people. The others are referred to as Dohar, while the cluster’s leader is called Ustad.

The dancers wear regular clothing but tiered handkerchiefs around their wrists and browse. They sometimes wear strings of bells around their ankles in unison in some places.

The Chati is played by the Ustad, and the Dohars typically play the Jharni, which is constructed of bamboo, to maintain the rhythm and pace. The beat is maintained in some areas by approval. The Ustad sings from the center. The Dohars surround him in a tight circle, singing the chorus of the song. The dancers expressed their sorrow through the motions of their heads, hands, and feet.

Watching the Muharrum moon marks the beginning of Jari dancing. Jari teams travel throughout the village, visiting various homes. For their performances, they are given cash or food. The various dance groups gather in Kerbela, the location chosen for their last performance on Ashura.

Kali’s dance

In the Kali dance, the dancer wears a black mask representing the goddess Kali, complete with her signature protruding ruby-red tongue, while doing this dance. The dancer carries a sword in one hand and a person’s bone in the other. The fact is that the drum is the primary instrument for this dance, expressing every valour and cruelty.

Kali dance. Wearing a black mask portraying the goddess Kali and her signature ruby-red tongue protruding, the dancer performs this dance. The dancer carries a bone belonging to someone in one hand and a sword in the other. The drum is the primary instrument for this dance, conveying every act of bravery and brutality.

https://sobbanglay.com/sob/khemta-nach/

Khemta dancing

Khemta songs, which are based on the tale of Radha and Krishna, are accompanied by the Khemta dance. The musical instruments consist of drums and cymbals. Any event could have featured khemta dances, which were formerly popular at weddings and pujas.

Although this is generally a women’s dance, eunuchs are connected to it in certain regions, and the United Nations agency is still preserving this art form. Sophisticated footwork and meaningful facial and eye expressions characterize khemta dances. The agricultural counterpart of the baijis’ or talented female dancers’ urban dance is this enjoyable dance.

The Lathi dance

The stick dance known as Lathi dance is carried out by groups of young people during Muharram. Brass cymbals and drums are often used to keep the rhythm and tempo. The youngsters wear tight attire and sometimes wear strings of bells around their ankles.

They are holding bamboo sticks that are about four or five feet long in their hands. They simultaneously carry cymbals, daggers, and swords. The club dance is a combination of sport and dance. The youngsters display their courage by engaging in a fake battle while armed with swords and sticks.

They skillfully rotate their sticks, moving them in time with the music either in front of or to the side of them, as well as beneath their legs or above their heads. A battleground is created by the violent collisions of the sticks. The percussionist is essential to this dance since he directs the dancers’ motions, speed, and rhythm. The fight, resolution, and rest are just some of the segments that make up this dance, which also includes an introduction to the Associate in Nursing program and completely distinct, aggressive postures.

The tempo starts slowly but gradually picks up speed before reaching a crescendo at the conclusion. The club members display their talent in the courtyards of residences, at road intersections, and ultimately at the mock city grounds during the first ten days of Muharram.

Dance with masks

dance with masks in the final days of Chaitra, the deities Shiva, Dharma Thakur, and Nada Square are revered everywhere. During those pujas, dancers present songs and dances while wearing masks that portray completely different deities.

In the nursing dance, cloaked dancers portray the Hindu deity in his fourth manifestation as a lion, while in the bola dance, cloaked dancers show a stiff body being eaten by vultures. Mukha Khel, a masked dance popular in north Bengal, involves people making their own masks out of wood, cloth, paper, and other materials. The characters range from regular farmers and woodcutters to kings and ministers.

The Rajbangshi girls of le mandarin do a ritual dance during droughts in which they worship Huduma Deo, the rain god. At night, they sort of squawk and exit the fields. They conduct a puja to Huduma Deo there. After that, they start to undress, dance, and sing.

Puppet dance

Despite how recent the tradition of puppet dancing is in Bengal; it is not proverbial. The main importance of puppets, however, is in Yusuf-Zuleika, a 15th-century epic. In Bengal, there are three distinct types of puppets: glove puppets, rod puppets, and string puppets.

An artist sings a song and makes the puppets dance in an attempt to mimic the song’s atmosphere while the musicians play their drums, cymbals, and flutes. The performer uses strings to manipulate the string puppets in order to make them appear to be the distraction.

String puppets and rod puppets are frequently used to perform narrative or Palagan dramas, occasionally based on the tales of Rama-Sita and Radha-Krishna. The modern social occurrences that make up these plays are also included. These plays’ main goal is educational. But they’re also quite entertaining together. String puppets remain popular in Nadia, while rod puppets are still used in the 24 Parganas of the province.

Male and female glove puppets attempt to dance. In the Midnapore and Burdwan areas of the province, some members of the Kahar class make a livelihood by doing puppet dances. An associate in nursing performing artist sings while manipulating the puppets in both hands. Although the tales are taken from the Purana, their entertainment value is prioritized over their religious value.

Children used to have puppet dances at their weddings or at their Anna pra Shana. Puppet dances were commonplace in north Bengal, Mymensingh, and Comilla, but this genre experienced a reversal at partition as many Hindu artists migrated to the province. Today, just one or two families in Brahman Baria make a living from this art.

The dance known as Raybenshe

Raybenshe performs a combat dance that resembles club dancing. The dancers wield ray banish, which are poles made of strong bamboo. The soldiers employ swords and spears together. In Burdwan, Birbhum, and Murshidabad, this dance was formerly common, and both Hindus and Muslims take part. The manual dexterity of the performers’ hands is the dance’s main draw.

Tribal dancing

People danced to lull or beat evil spirits, to prevent rot and disease, to induce rainfall for crop production, or to halt drought or famine. As society has changed, human actions have changed in a number of ways, resulting in differences in dance designs. The plain and unsmooth areas of East Pakistan are home to a wide range of tribes, including the Manipuris, Santals, Oraons, Murongs, Chakmas, Garros, Khasias, Kochas, and Hajongs.

Despite some modifications in the sustenance, nonsecular beliefs, and lives of certain of these tribes, there has been no fundamental change in their way of life. The majority of their food still comes from jungle fruits and roots, looking, and Jhum farming, and they still have a tendency to mimic their forefathers in their many cultural and non-secular festivals, even in this day.

On nonsecular celebrations, births, deaths, weddings, and other events, most tribes engage in dance, song, and music. They perform dances in ancient attire, either alone or in groups, accompanied by their own music. They make their own instruments. When their tribes are named, such as Santal dance, Garo dance, Manipuri Dance, etc., their square dances are given their names.

In addition to dancing for the building of houses, farming, and fishing, they also dance to commemorate the creation of humanity. During a drought, they perform dances pleading for rain and divine intervention. “The higher the dance, the higher the crop,” according to the Khasias. The drum, madal (a rather tom-tom), and flute are examples of musical instruments that are frequently employed as accompaniment.

The Chakma’s bamboo dance is very common. Cheralam is the local term for it. In this dance, two teams of men or women each hold two bamboos on either side of the group of dancers. By placing pairs of bamboos, they create a lilting tone. In rhythmic unison, the dancers leap between the two bamboos, making sure to jump before they collide. Unless the dancers are extremely skilled, they risk serious injury.

Contemporary dance

In addition to folk and traditional dance, other forms like hip-hop, salsa, b-boying, and Indian film dance—which is known as free style modern—are also performed in Bangladesh.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the diverse landscape of dance practices in Bangladesh is a testament to the country’s rich cultural heritage. The coexistence of folk, classical, tribal, and contemporary dance forms not only reflect the nation’s historical and geographical significance but also fosters a sense of community and collective identity. Through the rhythmic movements and graceful postures, dancers in Bangladesh convey emotions, tell stories, and preserve traditions, thereby perpetuating the cultural narrative of the nation. Furthermore, the evolution of dance practices, with the incorporation of modern styles, demonstrates the dynamic and adaptive nature of Bangladeshi culture. Ultimately, the significance of dance in Bangladesh lies in its ability to unite people across ethnicities, generations, and geographical boundaries, making it an indispensable component of the nation’s cultural fabric.

Bibliography

- “Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra’s Rashidul Hossain passes away”. bdnews24.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- “Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- Ahmed, Shabbir; Ali, Syed Ashraf (2012). “Eid-ul_Fitr”. In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Das, Joyce. “Borodin – Christmas in Bangladesh”. asiapacific.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Rahman, Wafiur. “Celebrating Christmas in Bangladesh”. dhakacourier.com.bd. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- “Historic Mosque City of Bagerhat”. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- “Ruins of the Buddhist Vihara at Paharpur”. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- “The Sundarbans”. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- “Baul songs – intangible heritage – Culture Sector – UNESCO”. unesco.org. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- “Traditional art of Jamdani weaving – intangible heritage – Culture Sector”. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- “Mangal Shobhajatra on Pahela Baishakh – intangible heritage – Culture Sector”. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- “Traditional art of Shital Pati weaving of Sylhet”. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- “Amazing Weird National Costumes”. www.nerdygaga.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

Ph.D.Dance (ICCR Research Scholar ) Guided by Dr. Ami Pandya,

Department of Dance, Faculty of Performing Arts, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Gujarat