PANDIT NIKHIL GHOSH and USTAD ALLAH RAKHA(An outward study on their styles and the cordiality they shared)

Subhadrakalyan

It has been of a great honour for the people of the century to witness that two of the most premium figures concerning the Tabla turned hundred this year. They have always been revered by all the musicians all across the globe as the first ambassador of the Tabla to the West. The cordiality between the two closest contemporaries of the Tabla, Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Ustad Allah Rakha can be justified by the notion of two people hailing from two different backgrounds, come floating straight by two opposite streams, moving at two different velocities with two different mental stature, to the contact point where both of them take up the same profession having the same point of interest with a great knowledge of the same philosophy, having the same thought processes going to the same direction, being fascinated by the same musical instrument belonging to one single genre of music – the Tabla. The two masters were noticed by the century as friends, compassionate about one another.

Though the first recorded name in the history of the Tabla is that of Miyan Sidhar Khan Dhadi, the recent research confirms the presence of a similar instrument, a pair of drums, one tuned to the tonic, the other bass, in sculptures dating back to over a thousand years. The word, Tabla, has not been present in recorded history or treatises prior to the time of Miyan Sidhar Khan Dhadi. Tracing the genealogy of the Tabla and the Guru Shishya Parampara, the Vedic way of the Guru imparting training to disciples, the name of Miyan Sidhar Khan Dhadi goes back to only ten or eleven generations from now. Such a dynamically significant drumming instrument had two of the greatest worshippers of the art of playing the same, Pandit Nikhil Jyoti Ghosh and Ustad Allah Rakha Qureshi, who spread and nourished two different branches of the evolution of the art of playing and teaching it. One marked feature in their approach as had been put forward by them, was that, both of them were primarily vocalists before opting for the Tabla and establishing themselves as the frontline maestros.

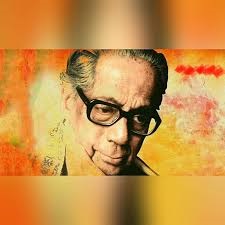

Pandit Nikhil Ghosh was born on the 28th of December, 1918 in Barisal, East Bengal, British India. Having completed his initial training from his father, he was subsequently taught by three of the greatest masters of the Tabla of the Farrukkabad school, namely, Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh, Ustad Amir Hussain Khan and Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa, beheld the twentieth century with the viewpoint of a Bengali musician, who, apart from being a great performer was also highly regarded as a teacher and a strong authority of all the different schools of the Tabla as well as the first representative of the Tabla to the Western world. The highly patronizing family of Ghosh helped him to develop an individual perception about the form of art he practiced, that comprised of a vast and dynamic knowledge ranging from the history of the Tabla to the different scientific techniques of playing it. It’s easily perceivable for the listeners of his music, he had a unique approach to keep up the authenticity of the style he would play. All his performances, as available in records, indicate toward his tendency to protect his knowledge from getting digressed toward the non-classicistic norms. The learners of music on the one hand observes him as an orthodox scholar of music and on the other hand accepts the notion, his introduction of new concepts into the subject surely points toward the fact, he had a futuristic aptitude toward music in mind. His marked conventional scheme of execution of his music must be believed to have been acquired from the training of Dhrupad he had received from his grandfather, Pandit Hara Kumar Ghosh. Also, his close association with the legendary vocalists of his time, such as, Ustad Fayyaz Khan, Ustad Aman Ali Khan, Ustad Mushtaq Hussain Khan, Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan and the likes developed his rich vocalism which later helped him to interpret the Tabla as a holistic instrument.

Pandit Nikhil Ghosh can be broadly justified as a successful student of the Tabla for his quest for knowledge has always been a point of interest of the learners of music of the current generation. He had had the fortune of learning from so many authentic men concerning the instrument that, it is rather impossible not to deliver a narrative study on the history of his learning.

Pandit Nikhil Ghosh first shifted to Calcutta from Barisal and stayed back there for the next two years receiving the lessons of the Tabla from Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh who would often go to Bombay; Pandit Pannalal Ghosh, the elder brother of Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, had already settled there with his career of playing the Indian flute on stage; for scoring background music for films. That way, finding his stay in Calcutta useless, Pandit Nikhil Ghosh too migrated to Bombay to start his career as a professional Tabla player. His training with Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh would definitely be continued. Now in Bombay, he started his career accompanying with his brother, the flautist, Pandit Pannalal Ghosh.

On this context of his attachment with his brother, I would like to remind the readers of his actively modernistic mind, underneath the rigidity toward convention that I have mentioned at the very beginning of the discourse. This argument can further be signified by the following anecdote.

Once the two brothers sat for practicing together elaborating upon Taalas like Jhoomra or Tilwada at the Vilambit or a considerably slow tempo. Pandit Nikhil Ghosh removed his hands from the Tabla and stopped playing while Pandit Pannalal Ghosh continued to play on mentally counting the rhythmic cycle. After a gap of fifteen minutes, both of them arrived pin-pointedly at the Sam or the starting point of the cycle while they counted it. However, the introduction of this fun element into practicing apart from indicating both of their imaginative attitude toward music, does suggest a revolutionary step of the Indian classical music taken. It is apparently contradictory to their background of learning Dhrupad, prevalent in their family itself, but their performances, as have been heard from various records, assert the recent point of analysis and vindicate that they had always been true to the existing convention even through their introducing some newness. On the context of his modernism, it would be rather unfair not to elaborate on some of the special features he introduced into the art of playing the Tabla strictly adhering to the tradition. His immensely intensified knowledge of vocal music helped him find the seven notes and twenty–two microtones of vocalism to have analogous to them in the Tabla, the seven major syllables and leading to altogether twenty – two syllables all the seven major ones getting permuted and thereby combined. He would also make a similar sound production as the instrument he would accompany, on the left hand drum with the help of the change of tension as supported by the wrist. Such exemplars of novelty within the existing convention are bound to be acknowledged to give rise to a full–fledged development of the Tabla during the century.

Let us again now put the focus on the finer points of his taking the lessons of the Tabla even further imagining a time when, in the Western world, Adolf Hitler would declare ‘Total War’, Operation Spring would devastate Canada, Anne Frank, the holocaust diarist would be captured and sent to Auschwitz concentration camp, and here in India, Mahatma Gandhi would maintain his hunger strike in protest against his imprisonment, Kushal Konwar would die as the first martyr of the ‘Quit India Movement’, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose would set up a pro-Japanese Indian government at Port Blair and Bombay explosion would occur in the Victoria Dock of Bombay; such unrestful incidents all across the world would not stop his fuming spirit as a musician heralding many successful learning experiences for him to come his way; when Pandit Nikhil Ghosh would come in contact with his next Guru, Ustad Amir Hussain Khan almost accidentally. It can thus be summed up, in response to the socio-political turbulence in both the worlds, Pandit Nikhil Ghosh’s quest for peace through music was aroused to its fullest extent.

It was an informal in-house concert where Ustad Amir Hussain Khan would perform, that Pandit Nikhil Ghosh attended with one of his friends. Hearing the veteran luminary of the Tabla for the first time, he was mesmerized, for, it was unbelievable for him that the Tabla could be played so artistically; it was a great musical experience for him, as Pandit Nayan Ghosh, the illustrious son of Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, would say. The power Ustad Amir Hussain Khan had created, with his performance, on Pandit Nikhil Ghosh’s mind remained undaunted till he was made to write a letter to his Guru, Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh. The letter expressed his doubts about his own taste on liking Ustad Amir Hussain Khan’s performance, at the same time revealing his intense desire to learn from him.

Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh, in response to that letter, heavily emphasized on the fact, Pandit Nikhil Ghosh should be going to Ustad Amir Hussain Khan for learning as early as he could, without even thinking for one single minute, for the former considered the latter one of the greatest masters of the Tabla at that time.

Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, by this time, became known as one of the leading masters of the Tabla and began to share the stage with his senior colleagues such as the vocalists mentioned before and the string-instrumentalists such as Ustad Allauddin Khan and Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan, as well as his contemporaries like, Pandit Ravi Shankar, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, Ustad Vilayat Khan and Ustad Imrat Khan.

Readers would be surprised to know, he had exceled in his art so much so that, he would often be approached by Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa, the world renowned master of the Tabla. The real incidents preceding the beginning of his learning from this great maestro are worth mentioning on this context.

In the olden days, all the music conferences would be held in an open space with temporary arrangements for the stage built up for the artistes on the dais and general people in the audience and with definite arrangements of loudspeakers; surely, they wouldn’t be blared. During the time of one such music conference, Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa, having finished his stage-show, while relaxing at the outside could clearly hear Pandit Nikhil Ghosh playing the Tabla. He was so attracted by the master strokes of the Tabla produced from the hands of the artiste that he could not resist himself from praising him and asking him to play one particular composition yet again. It would surely be quite a rare incident for those who witnessed it, for, Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa would not easily appreciate anyone.

Here, it is quite necessary to mention two more similar incidents. One day, Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa asked Pandit Nikhil Ghosh to play one particular composition; the one compose by Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh; over and over again and after knowing who had composed it on asking the former, he was all in praise for the composer. The other day, the same occurrence was made to be repeated while Pandit Nikhil Ghosh played a composition of Ustad Amir Hussain Khan. On knowing, he had learnt from the composer himself, Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa stated he shared a brotherly relation with Ustad Amir Hussain Khan.

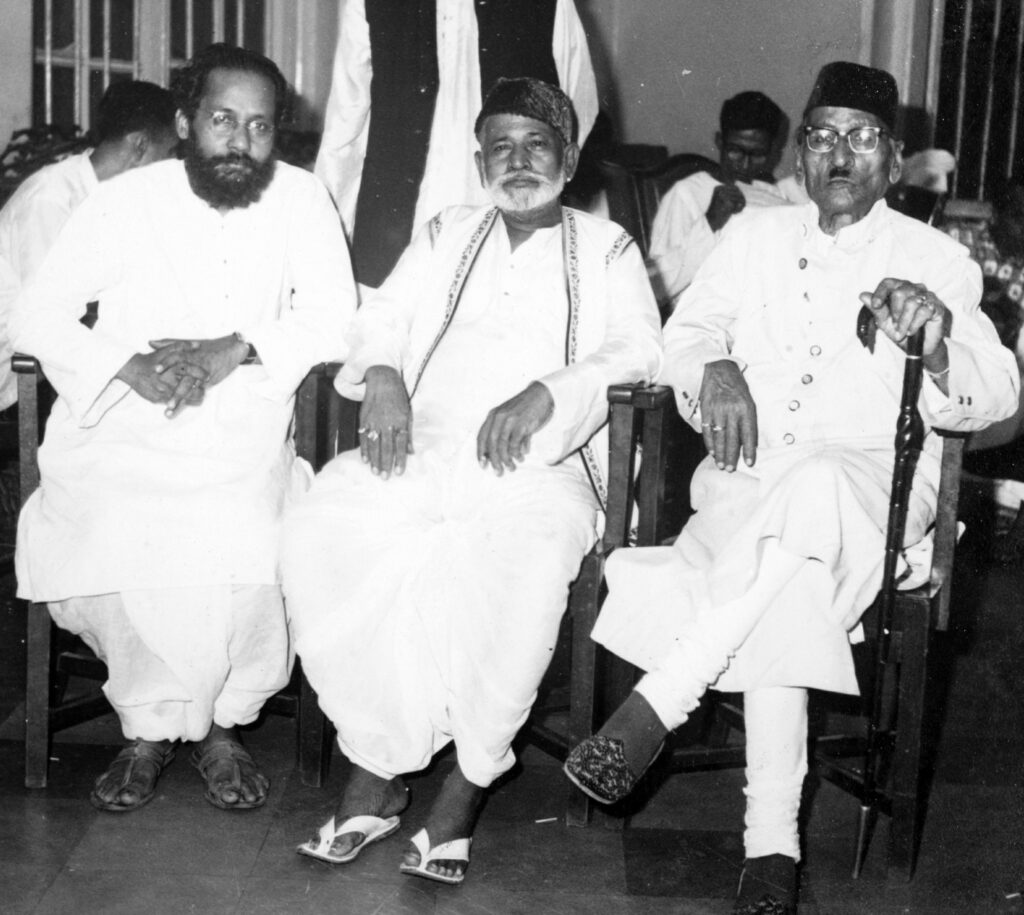

These two above mentioned events provide musicologists to identify with a distinct picture of the space where there would be the union of four great pillars of the Tabla from India, namely, Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa, Ustad Amir Hussain Khan, Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh and Pandit Nikhil Ghosh.

Shortly after such happenings, there developed a strong bond of friendship between Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa and Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, often looked up to with reverence by the latter. At one point of time, Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa repeatedly expressed his wishes to teach the young Pandit Nikhil Ghosh some intricacies of the subject, he had never taught anybody, before assuring him with the statement, ‘tumhari haath mein buzurgon ki nishaani hain,’ which meant Pandit Nikhil Ghosh’s hands spoke on behalf of the renowned masters. In the beginning he failed to construe the matter, for, he was doubtful if he would be able to bare the expenses of learning from Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa, for, he was always patronized by the landlords and the kings, but his doubts were cleared once he had a fair conversation with Ustad Amir Hussain Khan. It would be useful for the readers if the conversational details are given. The same has been noted from the discourse of Pandit Nayan Ghosh, the son of Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, as delivered particularly to me.

When Pandit Nikhil Ghosh approached Ustad Amir Hussain Khan with this specific query as to if he should learn from Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa, he said, despite being the student of Ustad Munir Khan, his uncle, Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa was quite knowledgeable about the Tabla, for, he had acquired the knowledge from both his paternal and maternal backgrounds and that Pandit Nikhil Ghosh should invite him to his house and learn from him as much as he could. While Pandit Nikhil Ghosh asked if he would be able to afford to learn from him, Ustad Amir Hussain Khan asked to carry on with his efforts.

This interview of Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Ustad Amir Hussain Khan was followed by another such interaction between Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh which took place through letters. On response to Pandit Nikhil Ghosh’s letter descriptive of all the proceedings, Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh wrote one single line – ‘If you succeed where I failed, I will consider it my success’ referring to the fact he could never learn from Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa in spite of all the necessary trials.

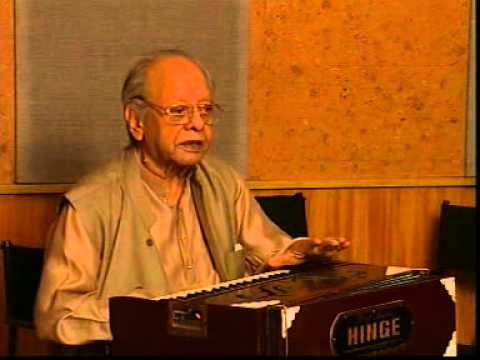

Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, having learnt from several maestros also developed himself to a teacher of the Tabla of the highest esteem. He made his greatest contribution to music through his founding his own institution of music, Sangit Mahabharati in 1956 and his accomplishing the work of authoring ‘The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Music of India.’ Pandit Aneesh Pradhan, one of his disciples recollects his memoirs with his Guru, Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, “My Guruji, Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, was selective as a teacher. While he headed a school of music that imparted training to the general public, he was very conscious of the disciples he chose. He was particular that the repertoire that he had so painstakingly collected from three gurus, namely, Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh, Ustad Amir Hussain Khan and Ustad Ahmedjan Thirakwa, should be inherited by those who would value this knowledge and consequently, he had few students. He taught them individually, most of the time in the late hours, post 10.30 pm, after he would complete his work for the day as the Principal of his school. This was the time he chose for his intensely personal practicing as well. Delivering the lessons to me did not necessarily follow a fixed pattern, that way, there were times when there would be several weeks between two formal classes taken by him. I was fortunate to have also been able to spend time in his proximity almost every day and I was also permitted to sit and observe his way of practicing. Often, he would stop playing on his own and ask if I knew a particular composition that he was playing at the time. If I did not know it, he would ask me to learn it right there. In addition, teaching was not restricted only to formal classes he took. It would happen even during concerts when I would be accompanying someone on the Tabla. He would signal me from the audience when he wanted me to play in a particular manner. Alternatively, he would advise me after the concert. He would also ask me to notify him when my recitals would be broadcast on the radio and he would then comment on performances. This would help me hugely in understanding the art of presentation. At other times, he would ask me to narrate my experience of a particular concert as a listener or young performer. He made it sure that my narrative was as detailed as possible. He would then comment on the way of my description which trained my skills of observation and helped me develop critical faculties. His knowledge of the melodic and rhythmic aspects also saw its way when he commented on ragas or melodic compositions.”

Now it’s the time to step into the next realm of the significance of the year, 2019, for that also marks the birth centenary year of another such master of the Tabla, Ustad Allah Rakha Qureshi, who would always be revered by all the keen learners of the subject. Pandit Nikhil Ghosh’s pre modernistic approach, keeping the tradition alive, towards the art of playing the Tabla, could successfully be contrasted with the rebellious steps Ustad Allah Rakha took to fully modernize it with a complex application of mathematics into it, an activity less done by the masters before his time.

Ustad Allah Rakha, was born in the village of Ghagwaal in Jammu-Kashmir, British India, on the 29th of April, 1919, to an agriculturist father. The young boy was only twelve years old when he was attracted to the sounds of the Tabla. His quest for an alternative life can well be discovered from the very incident of his running away from his home to learn the instrument from Ustad Miyan Kader Baksh. The enhancement of his musical skills was further supervised by Ustad Ashiq Ali Khan from whom, he learnt vocal music. His revolutionary contribution to Indian music ranges from his playing the first ever solo playing of the Tabla to be broadcast from the All India Radio to taking the first step to popularize the Tabla all across the world to collaborating with various artistes from the Western part of the world. His contribution to the Punjab school of the Tabla is inexplicable for he stands as the primary developer of the school as the one and only authenticated composer of various Bandishes, or the compositions, belonging to it, of the entire century. The Punjab School of the Tabla was still in its infancy with the life journey of Miyan Qadir Baksh as the style of playing the Tabla in the Punjab School was highly dominated by Pakhawaj repertory, till the time of Miyan Fakir Baksh, the father of Miyan Qadir Baksh. His performances make the note of his wizardry over the mathematical aspect of the Indian music, a point often overlooked by masters of music of the previous generation. His modernism is quite often proved from the various inartificially successful attempts to present mathematically justifiable compositions. Listeners of their music could draw a distinctive line of separation between the art of playing the Tabla before the century they were born in and after the birth of the new century as signified by them.

He is till date considered as one of the inseparable legendary duos of Indian classical music, the other being his long-time collaborator, Pandit Ravi Shankar. He developed a close rapport with Pandit Ravi Shankar both on and off the stage and toured together in the States. The pair became immensely popular all over the world and Ustad Allah Rakha achieved unmatched popularity as a maestro. In fact, as an accompanist, he gelled most perfectly with Pandit Ravi Shankar. His Western sojourns enabled him to interact with renowned percussionists, Buddy Rich, Mickey Hart and John Handy.

Ustad Allah Rakha, an extremely prolific teacher, has left indelible marks on his students. Pandit Sankha Chatterjee, the senior-most living disciple of Ustad Allah Rakha and also a junior colleague of Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, recollecting his intimacy with Ustad Allah Rakha, says, “He would teach me whenever he felt like doing so. I remember a particular incident of his teaching me during the security check-in at the Berlin Brandenburg Airport. The other time, he had taught me Rupak Taala for an entire night. One day,” he adds, “Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh had organized a concert inviting Pandit Samta Prasad, Pandit Anokhelal Mishra and Ustad Allah Rakha to play one after the other. Ustad Allah Rakha despite being terribly ill, continued to play for three and a half hours.” Looking back at the old times, he would also cherish the hours he had spent with Pandit Nikhil Ghosh. He remembers, “Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and I would often pass time chatting away; mostly discussing on compositions of the Tabla.” Pandit Yogesh Samsi, one young disciple of Ustad Allah Rakha, remarks, “Ustad Allah Rakha was a whole hearted giver. There would be hardly any time when he would not teach his pupils.”

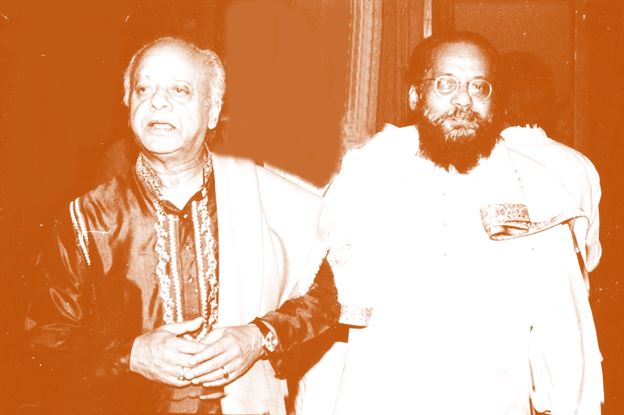

Ustad Allah Rakha was not unacquainted with Pandit Nikhil Ghosh before the former developed closeness with Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa. Both of them would regularly meet in music festivals; Ustad Allah Rakha would particularly invite Pandit Nikhil Ghosh to the music conference he would organize in memory of his Guru, Ustad Miyan Kader Baksh and Pandit Nikhil Ghosh would also call him back to perform at his institution for music, Sangit Mahabharati; but, it was when Ustad Allah Rakha had the knowledge of Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa’s stay at Pandit Nikhil Ghosh’s residence and he would invite him to his own residence for two or three weeks, their bond of friendship even found stronger grounds, for, now they had the same man to love apart from the same to instrument to worship. It is known, Ustad Allah Rakha never formally received lessons of the Tabla from Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa but what speaks of his utmost reverence for this legend is that he used to call him ‘Abba’ meaning the father. That way, Ustad Ahmadjan Thirakwa must be attributed to the honour of the man of the century who could whole heartedly influence the convergence of the two primary monumental figures concerning the Tabla. The friendship between Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Ustad Allah Rakha that often took new turns from several events such as this was fruitful enough for both of them to have legendary principles of teaching the Tabla, another quite an important aspect of the subject, to have a union – this incident is surely worth highlighting.

However, it cannot be possible for any of the observers of both of the maestros’ music to collide one onto the other, for, Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Ustad Allah Rakha prove to be complementary to each other with respect to the time both of them were carrying forward the instrument, Tabla. It is quite a lot significant to make an adequate argument at this moment that tradition is always prior to modernity. The greatest advantage for the development of the modernity in the subject, the Tabla, during the mid-twentieth century, the time of both the existing masters, was that, along with a modernist, there was a traditional practitioner of the same art who was the closest contemporary of the former. The evolution of the music in India during the twentieth century probably has to consider this particular incident as the most important one, for, it assures the gradual development of Indian music parallel to a successful trial of maintenance of the orthodoxy of the same. The Tabla, an instrument often admired for its dynamicity must be credited for having a legitimate improvement in the way of practicing it as supervised by two greatly close contemporaries – Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Ustad Allah Rakha, one authenticating the tradition of it and the other justifying the same with a modern viewpoint, one establishing himself a corollary to the other. That way, the existence of two great masters of the Tabla, Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Ustad Allah Rakha as contemporaries subtly contributed to two opposite dimensions of the art of playing the Tabla. The traditionally authentic and musically loaded style of Pandit Nikhil Ghosh brought about a fluidity and melodiousness to the Tabla while the avant-garde approach of Ustad Allah Rakha highlighted the percussive staccato execution.

Now that I arrive at the concluding segment of the discussion, it would be worth telling one particular tale that would fully assert their convergent thought processes to have divergent justifications for the same.

Once Ustad Allah Rakha posed a question to Pandit Nikhil Ghosh to convert a particular composition called the Gat by Ustad Haji Vilayat Ali Khan; the founder of the Farrukkabaad School of the Tabla; originally set in Tisra Jati, the division of each Maatra or each macro beat having three Anumaatras or micro beats, into Chatusra Jati, the division of each Maatra or each macro beat having four Anumaatras or micro beats, without changing the vocabulary. A prompt reply from Pandit Nikhil Ghosh exposed a hitherto unknown dimension involving mathematical feat. Pandit Nikhil Ghosh not only converted the composition into a four tier masterpiece alternating between Chatusra Jati and Tisra Jati with equal spaced gaps to arrive at the Sam with marked precision. Both shared the happiness together.

This stupendous but healthy competition within contemporaries has been seen in every aspect of art, culture, literature, politics and the likes all across the world, and it is this competitive relation within the contemporaries that has always lead to the creation of the gentility of an era. Had Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Ustad Allah Rakha focused on the same aspect of the Tabla, such upliftment of the subject and such enormous influence of the subject over mankind in the later years would surely have been impossible. It would be quite improper to elaborate upon the impact the two maestros of the Tabla created upon the century, without mentioning that the century had also seen both of them performing together on the dais once with the duet of Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, the first duo on the fields of instrumental music and the other time with the duet of Ustad Vilayat Khan and Ustad Imrat Khan, the brothers whose names are synonymous with the Sitar, a string-instrument from India.

It would be most appropriate to conclude with how Ustad Amjad Ali Khan comments on the contribution of both Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Ustad Allah Rakha, simultaneously sharing some of his memories with them of playing concerts together. “Pandit Nikhil Ghosh has had a great contribution to Indian music not only through his institution, Sangit Mahabharati, but also through his book, ‘The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Music of India.’ My father and I had played a lot many concerts with him even at The Dover Lane Music Conference, one of the most prestigious music festivals of India. He and I shared a very personal bond and I used to look up to him as my elder brother. We also honoured him with the Haafiz Ali Khan Award. Ustad Allah Rakha too was a distinctive maestro of his time. Apart from playing the traditional art of the Tabla, he showed his calibre as a music director in many films as well,” says Ustad Amjad Ali Khan.

I finally end the discourse acknowledging Pandit Nityanand Haldipur, one of the early disciples of Pandit Pannalal Ghosh, Pandit Yogesh Samsi, the disciple of Ustad Allah Rakha, Pandit Aneesh Pradhan, the disciple of Pandit Nikhil Ghosh and Pandit Sankha Chatterjee who all have provided me with the necessary facts that could be included in the article. On the outset, I thank, Mrs. Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay and Mr. Amit Chatterjee for arranging the session of my interview with Pandit Sankha Chatterjee. I also thank Mr. Srinjoy Mukherjee for making arrangements for my interviewing Ustad Amjad Ali Khan. I particularly thank Pandit Nayan Ghosh, the son of Pandit Nikhil Ghosh, and Mr. Ishaan Ghosh, the son of Pandit Nayan Ghosh for having helped me with minute details of anecdotes and sharing rare suitable photographs for this entire work.