The Dawn of Ectogenesis: Navigating the Societal and Ethical Frontiers of Artificial Womb Technology – SOURAV MUKUL TEWARI

Abstract

The development of artificial womb technology, known as ectogenesis, marks a profound inflexion point in the history of human reproduction. While the immediate clinical application is centred on dramatically improving survival rates for extremely premature infants, the wider implications of this technology extend far beyond the neonatal intensive care unit. This scholarly article explores the multifaceted landscape of ectogenesis, bridging its nascent scientific and engineering foundations with its complex societal, ethical, and cultural “soft impacts.” Drawing upon a case study that utilises speculative design as a tool for public engagement, we analyse how a public “protostage” emerges to deliberate on issues that transcend clinical data, such as shifting concepts of parenthood, bodily autonomy, and the very meaning of gestation. The research demonstrates that through imaginative engagement, the public actively constructs futures, often drawing on existing stereotypes and lived experiences to frame the technology as a solution for infertility, a tool for professional women, or even a political instrument. This paper posits that fostering a rich, multi-perspectival public dialogue is critical for the responsible integration of ectogenesis. It is through these open, creative inquiries—which a pragmatic ethical framework can facilitate—that society can collectively “rehearse” potential futures and shape a trajectory for this revolutionary technology that aligns with our deepest human values, rather than merely responding to its inevitable arrival.

Keywords: Ectogenesis, Artificial Womb, Speculative Design, Reproductive Technology, Bioethics, Public Engagement, Moral Imagination

1. Introduction

Emerging reproductive technologies stand poised to fundamentally reshape the biological, social, and ethical frameworks of human society. Among these innovations, ectogenesis—the development of an organism in an artificial environment outside the body—presents one of the most transformative potentials. The prospect of an “artificial womb” has long been the subject of science fiction, but recent scientific advancements have brought it to the cusp of clinical reality. Researchers, such as those at the Maxima Medical Centre in the Netherlands, are developing prototypes with the primary goal of serving as a sophisticated neonatal incubator, a “bio-bag” designed to significantly increase the survival rates of premature infants born at the cusp of viability, currently a group with extremely high mortality and morbidity rates. The technology aims to provide a more natural, fluid-based environment that more closely mimics the conditions of the maternal uterus than traditional incubators, supporting the delicate development of the lungs and other organs.

However, the conversation surrounding ectogenesis is not confined to clinical efficacy alone. The introduction of such a technology gives shape to our relationships, responsibilities, and our very ideas of family and what it means to be human. As with any disruptive technology, a critical public dialogue is essential for its responsible development and social embedding. Yet, traditional public engagement initiatives often fall short, struggling to move beyond quantifiable impacts like health outcomes and economic benefits to address the profound “soft impacts” on cultural, moral, and political norms. The abstract nature of these discussions, coupled with the difficulty people face in imagining future scenarios, often hinders a truly meaningful and comprehensive public deliberation.

This article argues that a novel approach is needed to facilitate this essential dialogue. Speculative design, a practice that uses fictive objects and future scenarios to provoke thought, offers a promising methodology for engaging the public in a creative and emotionally sensitive exploration of ectogenesis. By presenting a tangible, though non-functional, prototype of an artificial womb, designers can prompt individuals to engage in a process of “dramatic rehearsal,” trying out different courses of action and envisioning potential futures. The following sections will delve into the theoretical underpinnings of this approach, presenting a case study on an artificial womb installation and analysing the qualitative insights derived from public engagement with it.

2. Literature Review & Background: The Challenge of Imagining the Future of Reproduction

The discourse on emerging technologies is often bifurcated into a technical conversation among experts and a public debate that struggles to grasp the long-term, non-quantifiable consequences. For reproductive technologies in particular, this challenge is amplified by deeply held cultural and moral values surrounding life, family, and the human body.

2.1. The Limits of Traditional Public Engagement

Public engagement is a cornerstone of responsible innovation, yet its conventional forms are often critiqued for their limitations. Firstly, there is a tendency to overemphasize rational argumentation, which overlooks the crucial role of emotional and embodied knowledge in moral judgment. Issues as profound as the nature of pregnancy and parenthood are not solely decided by logic; they are deeply intertwined with feelings of compassion, responsibility, and justice. Secondly, the formats of these initiatives often treat public opinion as a static entity to be harvested, rather than an active, fluid process of moral deliberation shaped by continuous interaction and new information. Finally, as noted, both the public and professionals find it difficult to imagine unknown futures, which can lead to a narrow focus on immediate, tangible benefits, while ignoring the broader, more subtle, but equally important societal shifts.

2.2. Pragmatist Ethics and Moral Imagination

To overcome these barriers, scholars have turned to alternative theoretical frameworks. Pragmatist ethics, in particular, offers a valuable perspective. This school of thought posits that ethical frameworks are not pre-established but rather co-evolve with scientific facts and technological artefacts. The process of moral inquiry is therefore viewed as open, experimental, and creative. John Dewey, a key figure in pragmatism, conceptualised the public not as a pre-existing group to be consulted, but as an entity that “arises when emerging technologies affect others in ways that existing institutions and arrangements cannot handle the consequences of adequately”. The public becomes “active” when it begins a “reflective inquiry” into an “indeterminate situation”. This inquiry is a collaborative act where individuals use their “moral imagination” in a “dramatic rehearsal” to explore a plurality of possible futures. This is not merely an intellectual exercise but a creative one, where emotional reactions, desires, and aversions are used to evaluate the moral acceptability of potential scenarios.

2.3. The Role of Speculative Design

Speculative design provides a material and practical tool for this kind of “dramatic rehearsal”. Unlike traditional design, which seeks to solve a problem, speculative design aims to “pose ‘what-if questions with the intent of opening up a conversation about the kind of future people want”. By creating tangible, provocative prototypes of a possible future—like an artificial womb—it bypasses the need for abstract reasoning and provides a concrete focal point for discussion. This practice, borrowing from futurology and literary fiction, uses imaginative logics to present an abstract phenomenon in a way that is defamiliarizing and thought-provoking. The design does not dictate how things should be but rather aids imaginative thought as a means to discuss the present and the future we desire.

3. Current Scenario: The Artificial Womb and its Technical Feasibility

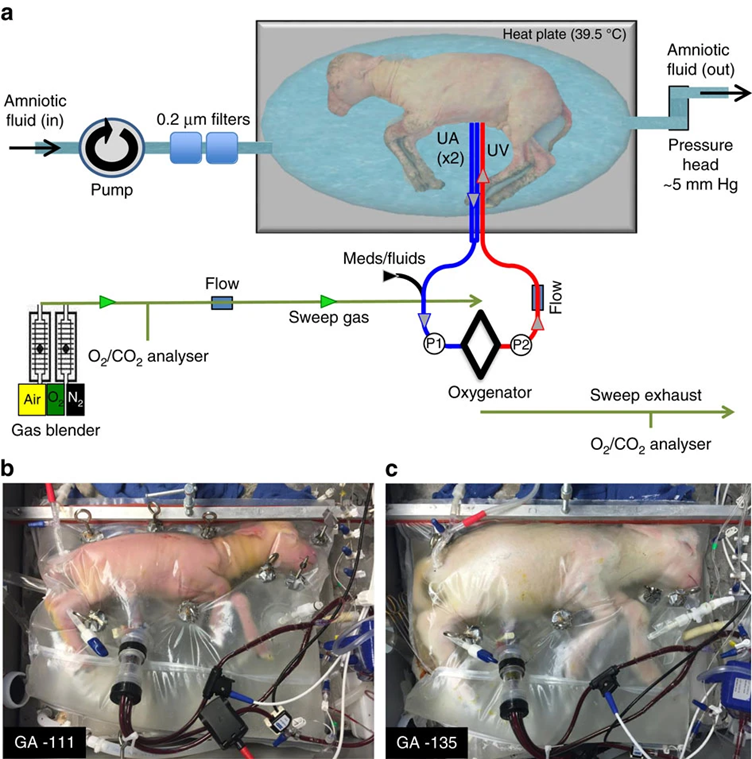

The scientific journey toward ectogenesis has been incremental, but recent breakthroughs have accelerated its progress. The primary technical challenge lies in replicating the intricate biomechanics and biochemistry of the natural uterus. A crucial breakthrough came from researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who successfully kept premature lambs alive and developing inside a “Biobag” system for weeks. This system, filled with a synthetic amniotic fluid, provided critical circulatory support and gas exchange, demonstrating the possibility of prolonged extra-uterine gestation.

Figure 1: A bio-bag ectogenesis system. The lamb fetus is suspended in a fluid-filled bag, connected to an external system for oxygenation and nutrient delivery. (a) Circuit and system components consisting of a pumpless, low-resistance oxygenator circuit, a closed fluid environment with continuous fluid exchange and an umbilical vascular interface. (b) The representative lamb was cannulated at 107 days of gestation and on day 4 of support. (c) The same lamb on day 28 of support, illustrating somatic growth and maturation.

The goal of such a device is to bridge the “periviable” period—the window between 22 and 24 weeks of gestation when an infant’s chances of survival are minimal, and if they survive, they face significant risks of neurological and developmental disabilities. An artificial womb would offer a sterile, controlled environment, minimising the risk of infection and allowing for precise monitoring of vital signs, nutrient delivery, and waste removal. While current research is focused on this limited-time, life-saving application, the very existence of the technology opens up a much wider speculative landscape.

4. Research Insights: Speculative Design in Action

To understand how the public engages with this technology, a case study was conducted on a speculative design installation of an artificial womb at the Dutch Design Week in 2018. The installation, created by the Next Nature Network, consisted of large, balloon-like spheres connected by tubes to a pink base plate, designed to be visually ambiguous and provocative. Researchers engaged visitors in semi-structured conversations to capture their reflections.

4.1. Engaging with What-If Questions

The study found that the majority of participants were able to “suspend their disbelief” and engage in the thought experiment. The installation’s physical appearance acted as a gateway to ethical reflection. For example, some participants focused on the practical implications, such as the logistics of administering nutrients in an external uterus. This practical reflection quickly led to deeper ethical questions: Would this technology be used for convenience? Should everyone who wants to have children be allowed to use it?. This process demonstrates how a tangible object can facilitate a journey from technical curiosity to profound moral deliberation.

4.2. The Power of Ambiguity

A key finding was the enabling power of the installation’s ambiguity. Because the prototype was an “ambiguous installation,” it required participants to “come up with their own frames of the technology”. These frames were highly personal and depended on the participants’ backgrounds and what they found important. For instance, the same installation was framed by one participant as a “beautiful solution for premature babies,” while another framed it as a “tool for career women”. These contrasting frames led to divergent moral evaluations, with the participant who viewed it as a “solution” approving of it, while the one who saw it as a “tool for career women” fiercely objected to its use. This highlights how the absence of a fixed narrative forces a more authentic and diverse public inquiry.

4.3. Scenarios, Stereotypes, and Lived Experiences

The research identified three primary ways participants questioned human-technology relations: through scenarios, stereotypes, and lived experiences.

- Scenarios: Participants used the technology as a starting point to craft full-fledged scenarios about a speculative future. One group of participants, for example, imagined a world where the artificial womb was placed in a nursery with a webcam, allowing a mother to “wave” to her baby on the way to a meeting. This process of “world-building” gave them ownership over a speculative future.

- Stereotypes: In crafting these scenarios, participants often relied on stereotypes to fill in the blanks. The “career woman” and the “malicious dictator” were common archetypes used to symbolize their fears about egoism, political abuse, and human instrumentalization.

- Lived Experiences: Participants frequently used existing practices and personal experiences as a “moral anchor” to evaluate the prototype. They compared the installation’s opaque, balloon-like spheres to the protective feeling of a natural womb. Others referenced the open, transparent design of current incubators to express concerns that the proposed design would prevent physical contact with the child.

Figure 2: A conceptual feedback loop of public engagement with speculative design. The tangible prototype triggers “what-if” questions, leading to moral reflection, which in turn informs how the public perceives the technology.

5. Challenges and Ethical Frameworks

The potential of ectogenesis is immense, but so are its ethical challenges.

- Bodily Autonomy and Choice: While the technology could offer reproductive freedom to those who cannot or do not wish to undergo gestation, it also raises questions about societal pressure. Will ectogenesis become a new standard, creating expectations for women to choose it for career or social reasons?

- Redefining Parenthood: If a fetus is gestated entirely outside of the human body, who is the parent? What are the legal rights and responsibilities of the biological donors versus the operators of the artificial womb? The concept of “personhood” itself may need to be redefined, with questions arising about when a child in an artificial womb is legally considered a person.

- Social Equity: The technology, at least initially, will be expensive and likely accessible only to the wealthy. This could exacerbate existing social inequalities, creating a reproductive “caste system” where a privileged few can outsource gestation, while others remain bound by biological limitations.

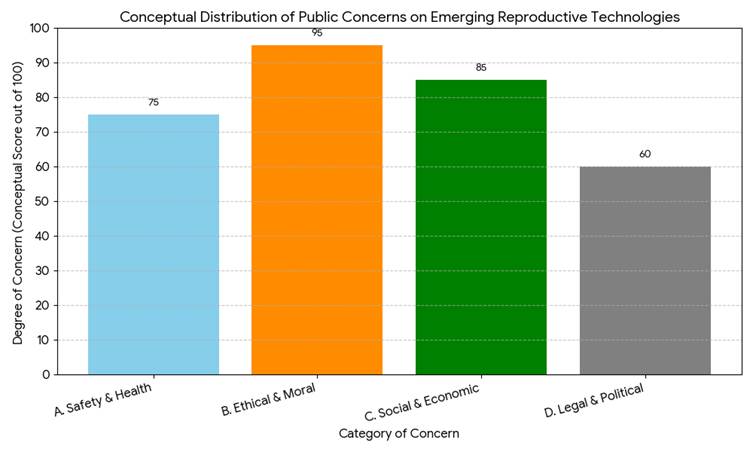

Figure 3: A conceptual bar chart illustrating the distribution of public concerns, with the “Ethical & Moral” and “Social & Economic” categories often ranking as high as, or higher than, direct health-related issues.

6. Future Scope and Conclusion

Ectogenesis is no longer a distant fantasy but a near-term reality with the power to redefine human life. To ensure its responsible development, a multi-stakeholder approach that goes beyond the laboratory is paramount. Speculative design, as demonstrated by the case study, offers a vital tool for this purpose. By allowing the public to become “creative moral agents”, it facilitates a process of collective sense-making that unearths the deeply personal and societal implications that clinical data alone cannot capture.

Future research should focus on refining speculative design methodologies to better address the inherent tensions between technical detail and ambiguity. The design must be informative enough to ground the conversation in reality but ambiguous enough to foster imaginative thought. Furthermore, exploring how different cultures and societies, with their unique values and norms, might frame and adopt this technology will be crucial for a global understanding.

In conclusion, the journey of ectogenesis from science fiction to scientific fact demands a corresponding evolution in our approach to public dialogue. By fostering spaces for “dramatic rehearsal,” where we can collectively try out and evaluate a plurality of possible futures, we can ensure that the advent of the artificial womb is not just a technological triumph but a human one as well. It is a creative, collaborative act of inquiry that will ultimately determine the meaning and shape of parenthood, family, and what it means to be human in the 21st century.

References

- Angheloiu, C., Sheldrick, L., & Tennant, M. (2020). Responsible Research and Innovation and speculative design: A novel method for upstream engagement. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 7(1), 1-22.

- Cuhls, K., & Daheim, C. (2017). The role of emotions in responsible research and innovation. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 4(1), 1-18.

- Felt, U., Fochler, M., Müller, M., & Strassnig, M. (2009). The speculative design practice. Design Issues, 25(4), 1-15.

- Fiorino, D. J. (1990). Citizen participation and environmental risk. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 15(2), 226-243.

- Keulartz, J., Schermer, M., Korthals, M., & Swierstra, T. (2004). The ethics of emerging technologies. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 17(2), 115-131.

- Kupper, F. (2017). Pragmatism, art, and public engagement with science and technology. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(6), 1637-1652.

- Nabuurs, J., Heltzel, A., Willems, W., & Kupper, F. (2023). Crafting the future of the artificial womb – speculative design as a tool for public engagement with emerging technologies. Futures, 151, 103184.

- Pau, C., & Hall, S. (2021). The future of the artificial womb. Science in the News.

- Roeser, S., & Pesch, U. (2016). The role of emotions in technological change. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 3(1), 1-15.

- Shelley-Egan, C. (2011). John Dewey and the pragmatist critique of public opinion. Social Epistemology, 25(4), 415-430.

- Stilgoe, J., Lock, S. J., & Wilsdon, J. (2014). Why should we promote public engagement with science? Public Understanding of Science, 23(1), 4-15.

- Swierstra, T., & te Molder, H. (2012). Risk and soft impacts. Handbook of Risk Theory, 1049-1066.

- Willems, W., Heltzel, A., Nabuurs, J., Broerse, J., & Kupper, F. (2023). Welcome to the fertility clinic of the future! Using speculative design to explore the moral landscape of reproductive technologies. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1-12.

About Author:

Name: Sri. SOURAV MUKUL TEWARI (W.B.G.S).

Department: The Technical Education, Training & Skill Development (TET&SD), Govt. of W.B.

College: Sir. Rajendra Nath Mukherjee Government Polytechnic.

Designation: Lecturer in Mechanical Engineering.

Email Id: smukul.amiable@gmail.com.

Mobile No: +91-6290445311