An Introduction to the Musical Concepts of Satyajit Ray

SUBHADRAKALYAN

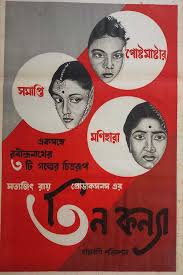

The world of Indian cinema experienced a storming change with the arrival of Pather Panchali in the year 1955, directed by a student of fine arts at the Kalabhavan, Shantiniketan and a former worker at the British-run advertising agency, D.J. Keymar, Satyajit Ray, the only Indian filmmaker to win the Oscar. However, Ray’s cinema would continue to reflect his own insight and depth of his knowledge on literature, society, history of culture and many more such things that concerned a medium that would appeal most to the human beings. Pather Panchali was surely a revolutionary film in the field of Indian cinema, pertaining to the films made in the pre-Pather Panchali era and the subsequent four films that Ray made, such as Aparajito, Parash Pathar, Jalsaghar, Apur Sansar and Devi, held a strong foundation over the early 19th century Bengal in varied dimensions. I distinctly omit Teen Kanya in the list, for, Ray has himself said, since the time of Teen Kanya, he himself would start scoring his films. Once again my inclusion of the point on the music of the films must be observed to be pertinent enough, for, Ray’s films would be incomplete without the music. The audience must be confused as to how much completely Ray could project the time he desired to show in his films, because, apart from the films, Pather Panchali, Aparajito, Parash Pathar and Apur Sansar, where Ravi Shankar scored the background, the other two, Jalsaghar and Devi were definitely an extravagant exhibition of Indian “classical” music by Vilayat Khan in the former and Ali Akbar Khan in the latter. I deliberately put the word “classical” within double inverted commas; and I am afraid, I will repeatedly do so, when I would particularly talk of it in the context of Indian music; because I never find the discrimination between the genres, demarcating between them basing upon social hierarchies, quite convincible. Ray has lamented upon the fact, both Vilayat Khan and Ali Akbar Khan would not comply with the demands of the film and make necessary measurements while scoring for the film. Ray also lamented on the fact, the maestros who all composed music for his films were not trained composers for which he would be in a grave trouble to fit their free-running music into his sequences. Ray has always maintained, the application of conventional Indian “classical” music in films is a waste of labor as the background music in most cases doesn’t have an independent identity as a piece of music. He believed, when conventional classicism imposed upon music is used in the music for a film as background music then the motif of the scenes seems to be less important as there is a diversion of focus and music gains more prominence thus compromising with the mood of the scenes it’s helping to be projected. Ray again proposed proposed, apart from the major direction, even if the director would not be actively involved into, editing or music-direction, the director must have the creative control over them. At some level, it could also be believed, the director understands best what tune can befit his shots and sequences, but on the contrary, not all film-directors are acquainted with music even in the least bit for which they could actually decipher the tune their shots and sequences could demand. Having been exposed to various forms of music, especially the classical music of the West, Ray found it easier to understand the adeptness and appropriateness of the application of his knowledge. The fantastic use of Gregorian Chants in the film, Shakha Prasakha, deserves a special mention for the particular application of such music on a particular scene could be explored in various angles. The discussion on that must be done some other time, for, now the focus must be on Ray’s musical concept in an entirety and not on any single aspect.

The readers must not be misguided with the notion; Ray was not much respectful towards Indian “classical” music. Ray always believed, the tradition of Indian “classical” music should be kept preserved, for, it was different from the visual art of the ancient India that exists in the carvings of the temples. Ray supported the concept of the evolution that had been taking place in Indian “classical” music and admired the innovative qualities of an individual artiste. Contradictory to his passionate love for Western classical music, he has admitted, in the West, it is not possible for an individual artiste to make improvisations thus keeping it restricted within the peripheries of the composition as perceived and designed by the composer, whereas, the scope for improvisation in Indian “classical” music allows individualistic interpretations of the phrases, leading to new establishments of the Oriental melodies. It must be mentioned, he himself did a sufficient use of Indian “classical” music in his films, Shatranj Ki Khiladi and Joy Baba Felunath, certain sequences in the films totally depending on the adeptness of Ray’s application of Indian “classical” music in them.

In spite of all this, Ray continued to believe, Indian music is non-filmic. He supports his belief with specific justifications when he says, the life of the Indians being much influenced by the colonial rule there is always a tendency to adapt to Western ways in them which heavily results in film-making, particularly when the story of the film is based upon urban life. The mixture that is significantly exposed in the ways of the Indians in the post-colonial era must be corresponded with music that is used in films projecting the post-colonial lifestyle of the Indians. It has already been mentioned, Ray would appropriately blend Oriental music with the Western one, whereas the former would be more prominent if the storyline would be set in a rural area and the latter in an urban one, Ray himself further making it quite clear, the more the plot of the story shifts from a rural background to an urban one, the less the director should use music.

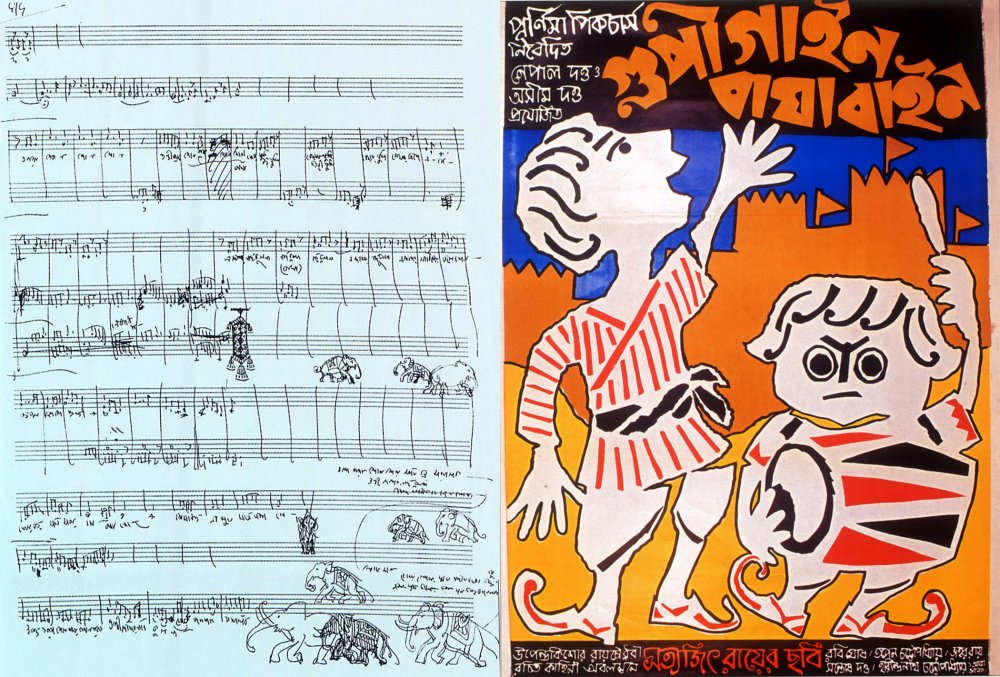

Since Teen Kanya, Ray himself started scoring for his films, though he has spoken about his lack of confidence during the initial days of him as a composer. Judging the parameters of the kinds of films they were, Ray’s adeptness of applying music and his dexterity as a composer could not be questioned. For many musicologists and personally for me, the perfect juxtaposition of the Western concepts of symphonies with the Indian melodies with major scale, and the tremendously well designed introduction of chromatic keys within them thus leading to the formation of two layers of scales; one, major and the other, minor; with proper introduction and conclusion of the movements, was something he got from his experience of listening to music of the West. His absolute precision as exhibited in his compositions was much similar to the music from the Classical period; majorly the compositions of Mozart; when the compositions would mostly be homophonic using a clear melody line over a subordinate chordal accompaniment. The counterpoint, another convention followed during the romantic period, would surely be found in Ray’s music, adeptly translated by Indian musical instruments.

Even when we see Ray to have worked with the virtuosos of Indian “classical” music, Ray would apply certain pieces of music that would enrich their compositions. In one of his interviews, Ray has said to Pierre-André Boutang, in Jalsaghar, he suddenly figured out, the composer did not provide him with the right kind of music that he wanted. In order to fulfill the demands of the sequence, he turned to his collection of records and played a composition of Jean Sibelius backwards. It certainly did complete the sequence. What might astound the readers more is that Ray quite clearly figured out the appropriate composition of Sibelius to fit in contrast with the composition of Vilayat Khan the keys not clashing.

In order to discuss how Ray was initiated into the Western music, we must trace back to his days, when he would remain infatuated towards Beethoven, reading about him in the ‘Book of Knowledge’, admiring his esoteric behavior and infuriated attitude. He would never feel the music of the West to be “bizarre” or “exotic”; rather, it would be the music that he would find close to his heart[1]. Ray’s finding the Western tunes familiar might have arisen due to his exposure to Rabindrasangeet and Bramhasangeet, the latter much influenced by the music of the West once Jyotirindranath Tagore, a talented pianist from the Tagore family of Calcutta started contributing to them with his knowledge of the culture and ways of the West. Ray’s strong foundation of musical concepts was planted, not instilled, within him, from the childhood, for he has himself has said, he belonged to a musical family where all the members were natural singers and his grandfather, Upendra Kishore Roy Chowdhury, a prolific violinist, an exponent of the Pakhawaj and a composer. He would particularly mention his “discovering” Beethoven, at the age of eight or nine, listening to Beethoven being his first experience to the music of the West. On the music of eighteenth century Europe proper, he commented, he was much influenced by the dramatic development of a composition that would first be exercised by Beethoven. His journey to “discover” Beethoven would make him contemplate over the humane elements that he would find in Beethoven’s sonatas.[2] “It is valid to speak of a Beethoven symphony in terms of universal brotherhood, or man’s struggle against fate or the passionate outpourings of a soul in torment. Western classical music underwent a process of humanisation with the invention of the sonata form – with its masculine first subjects and feminine second subjects and their interweaving and progress through a series of dramatic key-changes, to a point of culmination,” Ray would say while describing his experience of listening to Beethoven with his refined intellect.[3] A few years later when he would listen to ‘Ein kleine Nachtmusik’, a composition by Mozart, he missed the abruptness; a result of the inclusion of dramatic elements in them; of Beethoven’s compositions in it.

Even later, when he watched One Hundred Men and a Girl by Henry Koster, where in the conclusive part, he recalls, ‘Exsultate, jubilate’ by Mozart would be presented; he was moved and was astonished. He certainly didn’t find the work of Mozart similar to the works of Beethoven, but loved it for it was “civilized” and “sophisticated”. Having heard Mozart for the first time, he was much interested to know more about Mozart and started collecting records of his symphonies and concertos. However, even up to a certain point of time, the difference between Mozart and Beethoven would bother him until he realized Mozart’s talent was “rangy”. Ray has also admitted his love for Mozart would grow more and more once he would be acquainted with his operas, namely, ‘Don Giovanni’, ‘The Magic Flute’ and ‘The Marriage of Figaro’. The symphonies that pushed Ray through the journey of his knowing Mozart were his last four symphonies, Symphony No. 38 in D major, K. 504, often referred to as ‘Prague’, Symphony No. 39 in E♭major, K. 543, Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550, often referred to as ‘Great G minor’ and Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, often referred to as ‘Jupiter’.[4] Mozart’s appeal to Ray could be considered surprising, for, as Richard Taruskin would rightly comment in the second volume of “The Oxford History of Western Music”, “…in case of a symphony there is no mediating ‘objectively’ rendered stage character; there is only the ‘subject persona’ evoked by the sounds of the music, easily (and under romanticism, conventionally) associated with the composer’s own person.” However, Taruskin further adds in a new sentence, “There is no hard evidence to support the view that Mozart’s music contains a romantic emotional self-portrait; there is just the widespread opinion of his contemporaries, and the supposition that the composer, late in life, may have subscribed to what was becoming a conventional code.” For again, I would say, the justifiability of Taruskin’s statements depends upon the relative interpretations of the readers.

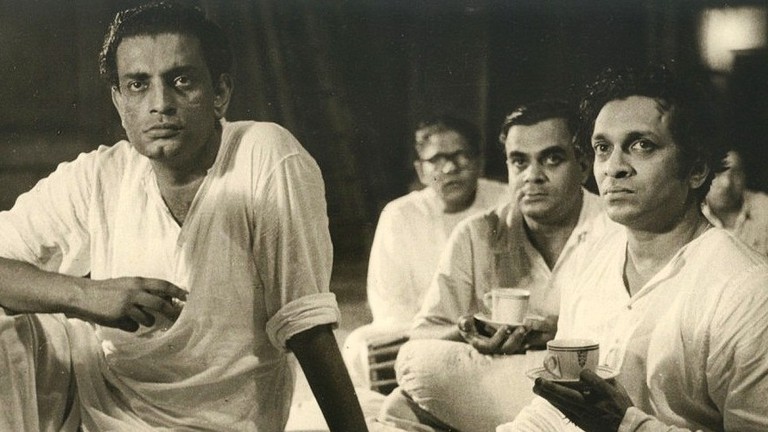

Ray’s exposure to the music of the West would be so very much influential upon him that, he would carry with him certain records of his own choice during his days at the Kalabhavan, Shantiniketan. A young boy Ray would always keep himself busy listening to music while the other people of his generation would go to the libraries to read books or indulge themselves in writing poems. Ray’s friend at the Kalabhavan, Shantiniketan, the extraordinarily talented painter, Dinkar Kaushik; the one with whom Ray shared a fifty year long association; who too went there to learn fine arts, would be first introduced to the Western music, Ray initiating him into it. Dinkar Kaushik would be much accustomed to the Indian “classical” melodies, having experienced the concerts of Abdul Karim Khan, Alladiya Khan, Fayyaz Khan, Ramkrishna Bua Vaze, Sawai Gandharva and Vinayakrao Patwardhan as well as a flamboyant flautist. The exchange of musical ideas between Ray and Kaushik would surely help both of them to discover the correlation between music and the rest of the world. Ray would often provide Kaushik with explanation of various compositions from the West, the first one being the Pastoral Symphony of Beethoven. Ray’s comment, “Amazing! That sounds like a Bach Fugue!” upon hearing Kaushik’s colorful tunes on his flute, would be an honest expression of his acute amazement.[5]

Supriyo Mukhopadhyay, one of Ray’s friends from Shantiniketan, would recall, Ray would be a favorite of Dr. Alexander Aronson, a Jew, who would lecture at Shantiniketan. Ray would take interest in discussing Western culture with Dr. Aronson, their discussion involving literature, fine arts and music. Dr. Aronson being a pianist would carefully explain the intricacies of the instrument to Ray. During his stay at Shantiniketan as a student at the Kalabhavan, Ray would most often visit the residence of Mukhopadhyay carrying with him the records of Arturo Toscanini, Paderewski, Jascha Heifetz or Fritz Kreister and the two would pass time listening to music seriously introspecting and contemplating each movement. In accordance with the account provided by Supriyo Mukhopadhyay, it must be believed, Ray’s enthusiasm for music was definitely not ostentatious but modest. [6]

In this essay, having discussed Ray’s foundation of music, I will briefly discuss how he perceived music to apply it in his film.

Ray considered, the impact of a film and a music-concert had somewhat a same impact on an individual and of course both would be likewise influenced by the amount of time given to it, because, he believed, literature being a different experience for one as one could choose to read it in a continuous manner, or to read it in installments or to skip and read, watching films and listening to music involve a continuous time of a couple of hours. He has particularly drawn such a proposition indicating towards the limited time spans of the performances of Western music, for, time to present Indian music often depends on the mood of the artistes and the necessity of the art. Ray proposed, when one watches a film again within a limited span of time, one is bound to feel the rhythm and the tempo of the film that emerges from the time it involves, which one overlooks the first time one watches it but is slowly attracted towards it upon having the experience of watching it over and over again. This leads to a point when one never thinks the film in terms of the story it is based upon but of the tempo and rhythm it features.

The interpretation of music has been differently judged by Ray. He believed, music when heard independently, its interpretation is mostly a product of the perception of music whereas, music when applied to films must be interpreted in terms of the visual impact. He justified his proposition with the facts, when an individual makes a movement, particularly in case of actions concerning works, the visual impact bears a structured, rhythmic tempo, and again, when a group of individuals move, it has a differently arranged tempo. Particularly for Ray, when he would be at the preliminary stage of thinking of making a film just having chosen a plot, he would design certain musical modes that would roughly match with the plot. The structure of the music being at its infancy would help the plot and the music itself to develop together slowly leading to a perfect formation of both. The beginning, the ending or the speed of the entire film would depend upon the movements of the music, both the film and the music complementing one another. The music would be even more perfectly applied during the time of shot-division, and would finally befit the entire film when it would be edited.

Ray would further continue his argument stating the fact, music as an independent form of art would differ from the kind of music applied to film as, independently heard music has a perfect cyclic count of the beats whereas, the music to films are what I previously said, “free-running” without a proper count of the beats. However, the music to films being entirely dependent upon the movements of the films has to be approached considering it in a holistic manner without demarcating between the genres wasting time and labor.

In the context of the comparative study between independent music and music applied to films, I feel, it’s necessary that I discuss how much of the necessity of music, if in any way, overpowers the intent of music. When Ray believes, the relativity of the interpretation of music to films clearly depends upon the visual impact of the films, it means, at some level, the art of music that has had a particular intent of appeasing the pleasures of the elite society since the early 13th century when; as a school of history has repeatedly suggested; India would be taken over by the Islamic rulers, has itself been translated to a necessity with the passage of time since then. If it is to be considered, the intent of music was a mixed purpose of communication and entertainment, then the communication would come before entertainment up to the 12th century in India, and a century later, the purpose of entertainment would overpower the one of communication, art being used as a device, thus leading to the emergence of popular culture, making rooms for political subversions and social hierarchies within it. A different school of history though suggests an altogether different hypothesis from where it could be easily derived, the origin of music varied from places to places and from communities to communities, pertaining to the socio-economic factors prevalent during such times, thus leading to the birth of an altogether different tradition. We must remember, the necessity of music came into being once the musicians faced an economic crisis which finally compelled to take music as a profession – a practice adequately supported and patronized by the people of the upper-class. The two hypotheses seem similar because, the two beliefs come to a somewhat same point. I leave the judgment on the relative interpretations of the readers. Histories being orally spread over generations particularly in India the facts above demand further verification with advancement in time when even more justifiable hypotheses could be derived with the availability of various newer pieces of information and the subsequent documents proving them. However, the intent being compromised has faced an evolution with time where in its maturation it’s only a need and not an experience for many. The necessity comes after the intent, when it might be justly argued, applying music complying with the necessity helps music to be functional and easy for better communication. Application of music in films provides the audience with an added experience of music when they are completely unaware of the very existence of it judging in terms of the defined conventions and are just being communicated to the aim of projection of life, something Ray’s cinema adequately features.

Ray has implemented his knowledge on music into his stupendous work of composing the background music. Though it has been suggested by Ray, the use of background music is more a necessity than any other aspect of it, for, “one has an audience in mind and one is always afraid that a certain change of mode will not be perceptible unless it is underlined by music” and “ideally one should be able to do without music”; the quoted phrases being from one of Ray’s interview to Pierre-André Boutang; Ray further suggesting the use of natural sounds and applying them creatively as the background music, Ray’s utmost expertise in this field would be most known by the kind of background music he would design for his films. The history suggests, in the past when silent films would be screened in the cinema houses, organ players would be rented to play the tune that could befit the scenes of the films. This had a major problem when different organ players would play different tunes according to their own perceptions of the sequences they would see on the celluloid. However, David Wark Griffith did not like such an idea and fixed certain musical pieces for his films and notated them for the conductor to conduct the orchestra. The pieces would not be original; Griffith would select parts of the compositions of Mozart or Beethoven. With the arrival of the talkies in Hollywood, the above formula started to be modified according to the demands of the films. Both in Hollywood and in the East that the dialogues were not to be overpowered by the excessive use of background music would always be believed by Ray. On the contrary he has mentioned, the background music is unable to complete a film if it is technically incomplete. The excess application of typed melodies would not enhance the type of emotion the director wanted to project and finally couldn’t, but only reduce the significance of such sequences furthermore. Ray was quite evidently against the conventional application of “happy music” in the sequences that bore a mood of pleasantness, “sad music” in the one that projected tragedies, an onomatopoeic “crash” in the ones that had sudden theatrical contradictions and “suspense music” in the ones that created tension within the minds of the audience. He always maintained his nature of being tremendously balanced and measured in his creations – be it films or music.[7]

Ray has particularly mentioned his works on music in the films, Kanchenjungha and Mahanagar, where it would be a challenge for him to mix the diverse moods of two different layers in each of the films. The contrast of the Anglicism and the lives in the Himalayan terrain, as projected in Kanchenjungha, would be perfectly complemented with music that comprised of certain modifications of the local folk music proficiently played by individual instruments of both parts of the world and translated into the concept of orchestration.

In Mahanagar, the challenges that Ray is said to have faced is again between the two layers of the plot of the film. The major female protagonist belonging to a lower middle-class family would be projected out in the city amidst the sophistication it bears parallel to the inner conflicts and contradictions of her. The sub-plot comprising of the ageing father also adds to the entire development of the story. Ray somewhere felt, the application of excessive background music would only hamper the concentration of the audience, but he finally complied with the theatrical mood of the film.

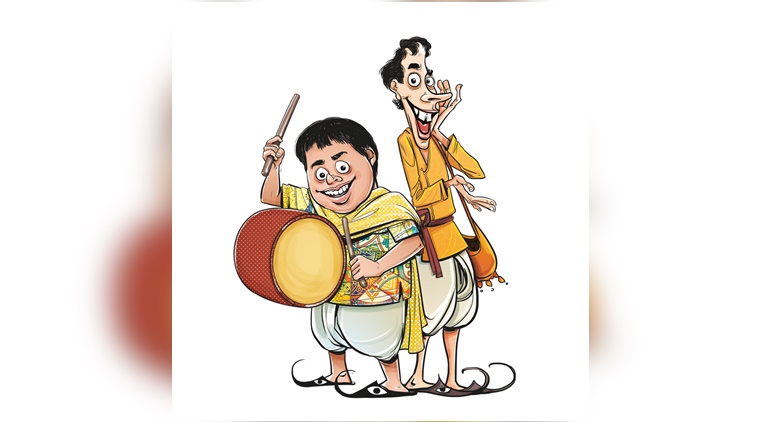

The most significant of the films of Ray where music plays a great part; apart from the films, Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne or Hirak Rajar Deshe; is the short film, Two. A major part of the music that Ray uses comprises of a flute playing with a chordal accompaniment provided by the Piano, probably played by Ray himself, clearly bears the shadow of the first movement of Mozart’s ‘Ein klein Nachtmusik’. However, the other flute played by the street-kid on screen bears an altogether different significance – the elaborated discussion done earlier in this essay, on Ray’s thought of applying music with respect to the projection of social stratification on screen, could be referred to in this context.

Ray’s unconventionalism in the field of composing music for his films has been a pathway to follow for many music directors that came after his time, though not everybody succeeded in fulfilling the purpose of music using it to a film. His understanding of music took his creations to a different level where it would be flawless, though not at all adhering to the convention mentioned above. Even in case of Ray composing songs for his films; a huge subject to be discussed in my next essays; he would be properly precise not using music as a device to present an exaggerated version of what he has wanted to propagate to people through his music. Ray’s music, not melodramatic; balanced, not exuberant; and functional, not decorative, has given the aura of the personality a different dimension with added glamour – something the other film directors of India contemporary to him and following him always admired to possess.

It would be most appropriate to conclude with Ray’s own words on how he finally puts his ideas on music to his films that ultimately culminates into a perfect juxtaposition of the two arts. Ray says, “I get my ideas fairly quickly – sometimes as early as in the scenario stage. I jot them down as they come. Usually they come clothed in a certain orchestral colour, and I make a note of that too. But the actual work of scoring has to wait until I am through with everything else, including final cutting.

“Of all the stages of film making, I find it is the orchestration of the music that needs my greatest concentration. The task may be lightened when I have acquired more fluency in scoring. At the moment, it is still a painstaking process.

“But the pleasure of finding out that the music sounds as you had imagined it would, more than compensates for the hard work that goes into it. The final pleasure, of course, is in finding out that it not only sounds right but is also right for the scene for which it was meant.” [8]

References:

- Satyajit Ray, PRABANDHA SANGRAHA, (Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd.), pp. 396-397

- Satyajit Ray, PRABANDHA SANGRAHA, (Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd.), pp. 396-397

- Satyajit Ray, OUR FILMS THEIR FILMS, (Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan Private Limited), pp. 49-50

- Satyajit Ray, PRABANDHA SANGRAHA, (Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd.), pp. 396-397

- Amitrasudan Bhattacharya, AAK DURLAV MANIK, (Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd.) pp. 27-30

- Amitrasudan Bhattacharya, AAK DURLAV MANIK, (Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd.) pp. 27-30

- Satyajit Ray, PRABANDHA SANGRAHA, (Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd.), pp. 70-71

- Satyajit Ray, OUR FILMS THEIR FILMS, (Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan Private Limited), pp. 70-71

Bibliography:

- Ray, Sandip (ed.), SATYAJIT RAY: SAKSHATKAR SAMAGRA, Kolkata: Patra Bharati, February 2020

- Ray, Satyajit, PRABANDHA SANGRAHA, Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd., September 2016

- Ray, Satyajit, OUR FILMS THEIR FILMS, Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan Private Limited, 2018

- Bhattacharya, Amitrasudan, AAK DURLAV MANIK, Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd., January 2014

- Chakravarti, Sudhir, BANGLA FILMER GAAN O SATYAJIT ROY, Kolkata: Gangchil, January 2016

- Taruskin, Richard, THE OXFORD HISTORY OF WESTERN MUSIC, New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.