Contribution Of Devdasis in BharatNatyam Dance

Nrityachuramani Rahul Dev Mondal

(Assistant Professor , Rabindra Bharati University,Department of Dance)

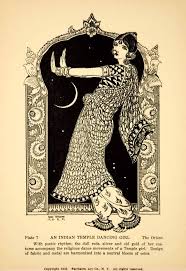

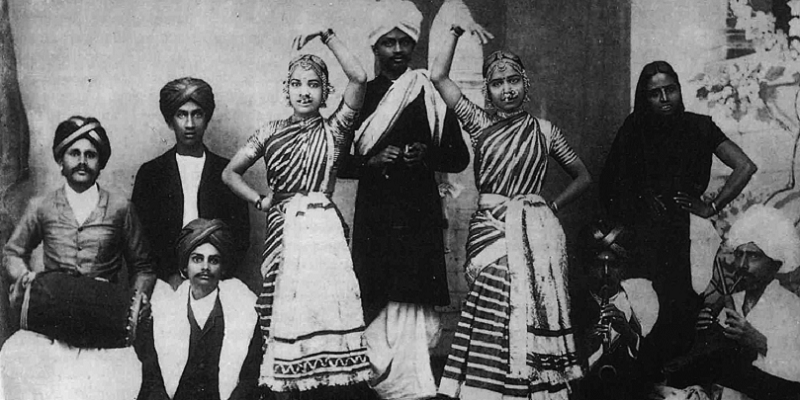

The generic Sanskrit term devadasi (“servant of god”) refers to a multiplicity of female communities, known by regional names such as devaradiyal (“slave of god”), bhogam (“embodiment of enjoyment”), kalavati (“receptacle of the arts”), and gudisani (“temple lady”). The women of these communities were the hereditary proprietors of a cultural practice that emerged as “Bharatanatyam” in the early part of the twentieth century. Devadasis performed in temples, royal courts, and at private soirees of the elite classes, often held on occasions such as marriages. Each of these contexts had its own set of dance and music compositions, though there was also a natural overlap, and technique and texts could sometimes be transferred from one context to another.

The most artistically developed of dances were performed in the royal court and not in the temple. The court or salon repertoire was variously known as chaduru or sadir (“performed before an audience”), melam (“troupe” or “band”), mejuvani (“entertainment for a host”), kaccheri (“concert”) and kelika (“play”) in nineteenth and early twentieth-century Tamilnadu and Andhra Pradesh. This court repertoire forms the basis of the modern art form known as Bharatanatyam. This suite, consisting of seven major compositional genres, was crystallized by four brothers, known as the Thanjavur Quartet in the nineteenth century, in the Maratha-period court of the city of Thanjavur. It displays a logical and gradual unfolding of the form, and provides a balanced representation of the two elements of nritta (abstract dance) and abhinaya (mimetic dance). The majority of dance compositions in the traditional repertoire were meant to be somatic exegeses on poetic texts that were usually erotic in nature. Longing, separation, and union were the core situations that characterized the poetic texts that were performed in courtly and salon contexts.

Devadasis were socially anomalous women. Some women from the devadasi community were ritually married to temple deities in a ceremony called bottukkattudal (“tying of the bottu [marriage emblem]”) and thus were considered to be set aside from the rest of Hindu society. After the bottukkattudal, they were usually entitled to a small income or tax-free land (called maniyam) from the temple or the feudal kingdom in the region. They often lived in matrifocal households, and usually took on male partners of their choice. The children born out of such relationships would live in the homes of their mothers, aunts, sisters and cousins. Female children could be dedicated for temple work or could live within the devadasi household as non-dedicated performers. Male offspring could become musicians for the women in the community or could leave the household after marriage. Many devadasi women did not undergo a marriage to a deity, but also performed in the context of court and home concerts.

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, a series of social reforms were ushered in by reform-minded Indians that dislodged devadasis from their traditional socio-cultural and religious roles. Devadasis were equated with prostitutes because they did not fit into the new paradigms of womanhood that were being enforced by Victorian colonialism and a nationalist resurgence of indigenous patriarchy that valued women’s domestic roles. Today, the art of the devadasi community has emerged on urban stages in India through a complex process that re-named and re-structured it, and the women of the devadasi community have been severely marginalized and socially and economically disenfranchised.

In South India particularly in Tamilakam the earliest inscription to mention a devadasi is as late as the 8th century C.E. The earliest literary sources to mention the association of devadasi with temple is in the hymns of Tamil Nayanar Campantar in 7th century C.E. The devadasi custom had to become an institution towards the end of the 5th and 6th centuries C.E. under the patronage of the Pallavas and the Pandyas.

The sources for the origin of the custom largely based on the literary records of ancient Tamils, particularly Tolkappiyam and Chilappatikaram. The practice of ritual dancing practiced by ancient Tamil tribe such as the Maravar hunters, and the gradual transformation of it under the influence of the brahmanical religion, seems to point towards the probable inspiration for the system temple dancing. In Sangam literature, the dancing women and prostitutes are frequently mentioned. But there was no evidence of temple women. During early medieval period onwards the devotional literature of Alvars and Nayanars from 6th to 9th centuries C.E. referred to women as celestial and human, offering worship to temples and to singing and dancing. The earliest literary source which mentioned the association of devadasi was the hymns of Tamil Nayanar Campantar one who lived in 7th century C.E. The Tamil bhakti ideologies of self- surrender and devotion to service had a huge impact on the society. It had a huge bureaucracy at its command amongst which the temple girls, who were employed in the service of God deserve special mention, since they formed significant officiating dignitaries. They were the most important ritual performers and no festive occasion was complete in the temple without the performance of the temple girls. Hence, the employment of these dancing girls became customary on the part of the devasthana (temple), which gradually institutionalized into a professional organization. The institution of devadasi was became an integral part of medieval temple organization.

In South India particularly in Tamilakam the earliest inscription to mention a devadasi is as late as the 8th century C.E. The earliest literary sources to mention the association of devadasi with temple is in the hymns of Tamil Nayanar Campantar in 7th century C.E. The devadasi custom had to become an institution towards the end of the 5th and 6th centuries C.E. under the patronage of the Pallavas and the Pandyas.

The sources for the origin of the custom largely based on the literary records of ancient Tamils, particularly Tolkappiyam and Chilappatikaram. The practice of ritual dancing practiced by ancient Tamil tribe such as the Maravar hunters, and the gradual transformation of it under the influence of the brahmanical religion, seems to point towards the probable inspiration for the system temple dancing. In Sangam literature, the dancing women and prostitutes are frequently mentioned. But there was no evidence of temple women. During early medieval period onwards the devotional literature of Alvars and Nayanars from 6th to 9th centuries C.E. referred to women as celestial and human, offering worship to temples and to singing and dancing. The earliest literary source which mentioned the association of devadasi was the hymns of Tamil Nayanar Campantar one who lived in 7th century C.E. The Tamil bhakti ideologies of self- surrender and devotion to service had a huge impact on the society. It had a huge bureaucracy at its command amongst which the temple girls, who were employed in the service of God deserve special mention, since they formed significant officiating dignitaries. They were the most important ritual performers and no festive occasion was complete in the temple without the performance of the temple girls. Hence, the employment of these dancing girls became customary on the part of the devasthana (temple), which gradually institutionalized into a professional organization. The institution of devadasi was became an integral part of medieval temple organization.

Devadasis were commonly found in most of the temples of the Chola period. A Inscription of the time of Kulottunga III (1215 C.E.) recorded that the king resumed about fifty six sacred festivals (tirunals) in the temple and also he also revived some of the old practices found mentioned in some earlier records. The process of the system further extended the system during period of Kulottunga III and Rajaraja III. It is evident from two inscriptions dated 1204 C.E. and 1235 C.E. They state that the system received royal support in the Tiruvorriyur temple. Another inscription recorded that Kulottunga III seated in the Rajaraja mandapa (hall) in the temple, enjoyed the dance performance of a devadasi in the Ani festival. A record dated 1235 C.E. of the time of Rajaraja III registered the presence of the king at the time of dance performance by a devadasi named Uravakkina- talaikkoli of the temple in the same mandapa. Much pleased with her performance, the king ordered that a village of sixty veli of land be granted to her. The later Pandyas also paid their keen attention for the institutionalization of the devadasi custom. An inscription dated 1203 C.E. recorded that queen probably of Jatavarman Kulasekhara I promoted the devadasi system in temple of Tirupattur and the system was further extended in the Sucindram temple around same period.

References:

Singh, A.K. 1990. Devadasis System in Ancient India. Delhi: H.K. Publishers and Distributors.

Swaminathan, A. 1992. Tamilaka Varalarum Panpadum. (in Tamil). Chennai: Deepa Pathppakam.

Tarachand, K.C. 1991. Devadasi Custom: Rural Social Structure and Flesh Markets. New Delhi: Reliance Publishing House.

Thurston, Edgar and K, Rangachari. 1987 (Rpt. 1909). Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Vol. II- C to J. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

Vijaisri, Priyadarshini. 2004. Recasting the Devadasi Patterns of Sacred Prostitution in Colonial South India. New Delhi: Kanishka Publishers, Distributors.

Singh, A.K. 1990.p. 24.

Altekar, A.S. 1959. (Rpt. 1983) The Position of Women in Hindu Civilization. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 182- 83.

Narayanan, M.G.S. 1973. “Handmaids of God”. in Aspects of Aryanization in Kerala. Trivandrum.

Jeevanandam.,, S. 2011. “The Sacred Geography of Medieval Tamilakam- A Study of Saiva and Vaishnava Temples”. in Birendranath Prasad. Monasteries, Shrines and Society: Buddhist and Brahmanical Religious Institutions in India in Their Socio- Economic Context. New Delhi: Manak Publications

Author :

Nrityachuramani Rahul Dev Mondal

(Assistant Professor , Rabindra Bharati University,Department of Dance)