(An outward study on their styles and the cordiality they shared)

SUBHADRAKALYAN

Indian music would often be classicized by a social hierarchy. This particular restriction, though needless, inflicted a strong punishment upon Indian music, for which, it was kept limited within the practitioners of Indian Classical music. Music has been witnessing a different wave to set into it for quite a long time since the onset of the period, when musicians would find it relevant to influence Indian music with Western inputs. However, the sole objective of these musicians was to reach out to a larger mass as music would be kept limited within a particular periphery of audience by the traditional classical musicians of the country. The most fruitful example of such an experimentation originated from Bengal with Rabindranath Tagore. Eventually, a handful of Bengalee musicians started moving to the different parts of the country, especially to the Western part of the country, more precisely to Bombay, to spread the form of music that was different from the existing form of traditional music and was much closer to the popular culture. These extraordinary musicians who first thought of freeing music from the boundaries of meaningless classicism imposed upon it by the traditional classical musicians of India were the ones who excelled as playback singers in films or were popular for non – film songs or both. It is an overwhelming fact for many Indians and even people living abroad, this year, it’s the centenary birth year of two of the most renowned popular musicians, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay and Manna Dey, who won the hearts of people all across the globe with their music, their personality and their humanity.

Hemanta Mukhopadhyay was born in the house of his maternal grandfather in Varanasi on the sixteenth of June, 1920. During the early 1900s, his family migrated to Calcutta, where he attended Mitra Institution in Bhowanipore. His days in the school even became more significant as he met his friend, Subhash Mukhopadhyay there. The irony that strikes us is that, Subhash Mukhopadhyay, the one who came to be known as one of the foremost Indian Bengali modern poet, would sing in his schooldays, whereas, Hemanta Mukhopdhyay, whom the world knows as one of the supreme luminaries of music, would be a litterateur with his short stories published in the Bengali magazine, Desh. Bengal would have lost a mellifluous voice had Subhash Mukhopadhyay not taken his friend, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, to the All India Radio, Calcutta, in the year, 1935. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, then a student of class IX, recorded a song, ‘Amar Ganete Ele Noboroopee Chirntoni’ for the All India Radio, Calcutta. Two years later, in the year, 1937, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay cut his first gramophone disc under the label of Columbia Records, where he sang, ‘Janite Jodi Go Tumi’ and ‘Bolo Go Bolo Morey’. The popularity of the disc lead him to record non-film discs for Gramophone Company of India, every year till 1984. His breakthrough as a playback singer was observed in the film ‘Nimai Sannyas’, in the year, 1941, the year Rabindranath Tagore passed away and a time when the World War II was going on in a most ferocious manner. A few years later, in 1944, he first recorded his songs, ‘Katha Koyonako Shudhu Shono’ and ‘Amar Biraha Akashe Priya’, which were his own compositions. The fact that is quite contradictory to the rising graph of the career of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay was that he couldn’t sing at the first concert of his life, where he was invited to sing. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay has later described the event in a TV interview stating, those days, concerts would be mostly organized by several Universities where the mythical performers of the time such as, Pankaj Kumar Mallik, Sachin Dev Burman and the likes would be invited. On one such concert, he was invited as his records released prior to it went popular; however, he had to come back without singing as Pankaj Mallik, the more famous singer of the time had arrived and captured the dais.

Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would equally succeed as a music director for the songs he would tune would be quite versatile. Right from 1944, the songs he would tune would be quite close to his simple yet a holistic approach to music. Without inflicting much of classicism in his compositions, he would rather believe in simplifying his tunes thus taking it closer to the emotions of the public. The simplicity in his music, the height of emotional content filling it on the top of it, would be a reflection of his simple lifestyle. His casual walks on the streets of the Southern part of the city in the morning wearing a white shirt and a dhoti would still be remembered by his closest ones as well as the ones who would admire him from a distance not daring to directly talk to him.

Hemanta Mukhopadhyay migrated to Bombay in 1951, soon after the Independence of India, to join the Filmistan studios. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, Hemant Kumar in Bombay, soon blossomed as one the most successful music directors of the country. Mr. Shashadhar Mukherjee of the Filmistan studios started producing films with Hemant Kumar as the music director. Having established himself in Bombay, Hemant Kumar first scored the music for the film, ‘Anandamath’ that was directed by Hemen Gupta, Not a successful motion picture at the box office, the film did not get Hemant Kumar the success as a music director. The next film from the same production house, ‘Shart’, that was directed by Bibhuti Mitra, was equally a flop. ‘Samrat’, the next film too couldn’t manage to do any justice to the songs that he composed. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, as he has written in his autobiography, would plan on returning to Calcutta, but the film, ‘Nagin’ that was directed by Nandlal Jaswantlal brought him the perfect fame as it was an extraordinary soundtrack that he scored for the film. The success of ‘Nagin’ held him back in the Filmistan studios for many more films to come. However, Hemant Kumar finally decided to start his own production house which got him subsequent failures which finally lead him to head back to Calcutta.

Somehow he started working for the films of Bengal simultaneously with his works for the films in Bombay. In 1955, he scored music for the Bengali film, ‘Shaapmochan’ starring Uttam Kumar. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, in one of his interviews has said, ‘It was quite difficult for me to set the tunes for Bengali song as I was aloof from Bengal for a long time (referring to his works in Bombay); whatever tune I composed seemed to be unattractive. As I was terribly running short of time, I finally reconciled to my lot and kept those tunes as they were done the first time.’ The rest is probably history. The world knows about the numbers. The film paved the way for the pair of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay and Uttam Kumar, the former lending his voice for the latter on screen to move further with many successes to come its way.Its absolutely worth mentioning, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay was the music director to the film, ‘Kach Kata Heere’ that was directed by Ajay Kar, where he didn’t use even a single song and scored the music to the entire film basing upon the background music.

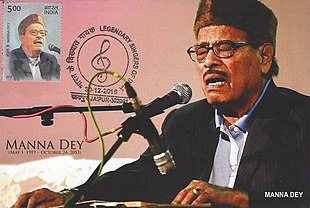

Unlike Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, Manna Dey, his closest contemporary had an eventually late start in rising as the prolific singer he came to be known as later in his life. Manna Dey was born Probodh Chandra Dey in the northern part of Calcutta on the first of May, 1919. Manna was a modified version of his nickname, Mana, a name easier to pronounce for people in Bombay when he migrated there in 1942. Though trained under his uncle, the renowned blind singing star of Bengal, Krishna Chandra Dey, mostly referred to as Kana Keshto, Kana meaning blind, Probodh Chandra Dey would pursue sports in his initial days, wrestling being his personal favourite. However, Manna Dey came to enter into the fraternity of music as his friends and the Principal of his alma mater, Scottish Church College, some kind of forcibly persuaded Dey’s uncle to allow him to sing in an intercollegiate singing competition. Dey’s uncle was somehow not sure about his nephew’s aptitude of and inclination to singing, but was assured by Dey’s friends; he would sing for them, the songs of his uncle and the mythical Sachin Dev Burman during the free hours of the college. He finally delivered his consent for his nephew to sing when the Principal of the college, Rev. Dr. William Spence Urquhart wrote to him, “Sir, it is our motto to find out the hidden talents of the student, just an approach to help them have the right exposure. Who knows which oyster bears the pearl! So, the college authority will be grateful to you if you kindly allow Probodh to participate in the forthcoming intercollegiate music competition. Hope your good self will consider the case.” His astounding performance and the subsequent success was followed by his intensive training of Indian Classical Vocal music under Miyan Dabir Khan, the last of the descendents of Miyan Tansen. In the year, 1942, Manna Dey migrated to Bombay as an assistant to his uncle who established himself as a music director there. His training of classical vocal continued under Ustad Aman Ali Khan, Ustad Abdul Rehman Khan and Ustad Ghulam Mustafa Khan. Manna Dey first sang song for the film, ‘Tamanna’. Once his uncle would compose a song but would not find the appropriate male voice that could execute it. However, tired with looking for the perfect voice and still not having found one, Krishna Chandra Dey tried his nephew out for the song. The song was actually a duet. The debutant little girl who sang with Dey came to be known prominently as Suraiya in her latter days. Among the other films of those times, ‘Amar Bhopali’ and ‘Ramrajya’ were the film that really cultivated the talents of Manna Dey. The music director of the film, ‘Ramrajya’, Shankar Rao Vyas, consulted Krishna Chandra Dey to sing a song. He refused to lend his voice to any actor on screen other than himself. However he got the work done when Vyas on his suggestion tried out the voice of Manna Dey. Such incidents actually paved the way for Manna Dey to be one of the most successful playback singers in future. He had to wait to get the opportunity to sing for the hero, for, as S.D. Burman also said to Manna Dey during the days he would work as an assistant to Burman that he wasn’t gifted with a voice for the hero. Much later, even in the films in Bengali, Manna Dey was heard to sing for the hero, when already Mohd. Rafi in Bombay and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay in Calcutta would establish their voice for the hero. In the films of Bombay, he finally got established as a playback singer once the song, ‘Upar Gagan Vishaal’, was a hit. The song tuned by S.D. Burman, was able to exploit the trained voice of Manna Dey which helped him to sing for any actor on screen with perfect adeptness.

Manna Dey would be adept at singing any kind of a song ranging from the types of the ones based on Indian Classical melodies to the ones that were quite funnily portrayed on the screen. The song, ‘Lapak Jhapak’, a composition of Shankar-Jaikishan, from the film, ‘Boot Polish’, were a perfect blend of classicism and fun where the classicism lies in the way the song is introduced through some improvisations on the Indian raga, Darbari Kanada, and the fun lies the way David sings it on screen. The same experiment has been repeated by S.D. Burman in the film, ‘Manzil’, when Manna Dey would sing his composition, ‘Na Banao Batiyan Hato Kahe Ko Jhuti’ which would primarily be based on the Indian raga, Bhairavi and would be sung in an apparently comical manner by Mehmood on screen. Manna Dey would be the first preference for any music director if the composition was based on Indian Classical melodies, specially the convention of singing the Tarana. The songs that hold the boldest example of such preferences upon Manna Dey are, ‘Laga Chunri Mein Daag’, a composition on the Indian raga, Bhairavi, from the film, ‘Dil Hi To Hai’ and ‘Bhor Aayi Gaya Andhiyara’, a one on the Indian raga, Alhaiya Bilawal, from the film, ’Bawarchi’. His expertise on the tradition of classical music of India would be most prominently proved when he would be heard to sing a duet with Bharat Ratna Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, for the film, ‘Basant Bahar’, the number being, ‘Ketaki Gulab Juhi’. Manna Dey’s adeptness to sing for drunk people on screen has also been proved by him several times, particularly for the songs, ‘Ei Duniyay Bhai Shob e Hoy’ from the film, ‘Ekdin Ratre’, Chhabi Biswas singing it on the screen; ‘Emon Bandhu Ar Ke Achhe’ from the film, ‘Dwip Jwele Jai’, Anil Chattopadhyay singing it on the screen; and, ‘Ta Bole Ki Prem Debe Na’ from the film, ‘Mouchak’, Uttam Kumar singing it on screen. Manna Dey would also be known for singing songs on sports, football being the primary of them. The song, ‘Shob Khelar Shera Bangalir Tumi Football’ from the film, ‘Dhanyi Meye’ and the song, ‘Khela Football Khela’ that he sang regretting the death of sixteen football fans in a riot at the Eden Gardens stadium in Kolkata on the sixteenth of August, 1980, clearly indicate the insight that Manna Dey possessed on the particular sphere. Suparna Kanti Ghosh, the son of the illustrious music director of Bengal, Nachiketa Ghosh, tuned the song ‘Khela Football Khela’ was but it’s even more appropriate to mention, he tuned two of the most widely known songs, the phenomenal hits, the ballads, ‘Chhoto Bon’ and ‘Coffee House.’ Suparna Kanti Ghosh, in the context of the occasions of Manna Dey singing the two songs, says, “Manakaku (that’s what he called Manna Dey) told me having given me the lyrics that he would only sing the song if he liked the composition. He also told me that I must not get disheartened. On my way back from his residence, aboard a bus, the tune of the first few lines came instantly. He too was impressed on hearing it. The rest remains history. The success of ‘Chhoto Bon’ boosted up my confidence and that led to the success of ‘Coffee House’. In an opinion poll entitled ‘Twenty Best Bengali Songs Ever’ conducted by BBC, it got the fourth place.” ‘Chhoto Bon’ and ‘Coffee House’ still remain the foremost among the most relevant songs to the hearts of the people, for the former expresses the personal tragedy in the life of full on professional and the latter the nostalgia of most people who still miss being together and chatting away.

The musical plays such as, ‘Rami Chandidas’ and ‘Sriradhar Manbhanjan’, vehemently proved, Manna Dey would equally accomplish himself in singing songs in the convention of Keertana, that he is believed to have learnt from his uncle, Krishna Chandra Dey. On the contrary, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would not participate in such traditional musicals; except for once in ‘Mahishasura Mardini’, an event broadcast from the All India Radio, Calcutta, on the early morning of Mahalaya, in his earlier days, and a reinterpretation of the same, titled, ‘Durge Durgati Harini’ in 1976 where he composed the songs; but would be premium choice to be a part of the musicals of Rabindranath Tagore, such as, ‘Shyama’, ‘Chitrangada’, ‘Shapmochan’ and the likes.

Rabindranath Tagore died in 1941, the year both of them turned twenty-one. The impact the bard left on these two youngsters was incredible in its own right. Manna Dey would however not record as many songs as Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would in his life, yet, both of their contribution to the sphere of Rabindrasangeet would be remembered by people forever. Not really conventionally trained to sing the songs of Tagore, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay tried out to sing them with the help of the notations provided to him by one of his mentors, Shailesh Dutta Gupta. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would quite consciously follow the ways of his senior, Pankaj Kumar Mallik, in his initial days, but would soon develop an incredible individuality in him. He would first record the songs of Tagore in the year, 1944. The two songs he first recorded were, ‘Keno Pantho E Choncholota’ and ‘Amar Ar Hobe Na Deri’. Later on, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would among the few ones who would take the initiative to popularize Rabindrasangeet. He would most popularize it through films. The films of Tarun Majumder would feature most of the songs of Tagore sung either by Hemanta Mukhopadhyay himself or any of his juniors under his direction. His method of executing a song by Tagore would be surely be followed by many of his juniors and is still followed even today.

Though during the last century, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay was one among the people who recorded maximum number of songs of Tagore, his closest contemporary, Manna Dey would not be heard to sing the songs of Tagore as much. Alak Roy Chowdhury, a junior colleague of both Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would say in this context, “The Music Board of Visva Bharati would be quite conservative in preserving the purity of the songs of Tagore. Those days, before publishing a recorded version of any song of Tagore, the record was to be submitted to the Music Board. The subsequent approval, depending upon many external and internal conditions, would finally allow the record to be published. Manna Dey, unlike Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, was not ready to accept such conditions, and he eventually withdrew himself from publishing his record of Rabindrasangeet.” It could be assumed a well trained singer, Manna Dey, was quite right in not publicizing his executions of Rabindrasangeet for the traditional limitations externally imposed upon the subject would surely bother him after a certain point of time. However, a select few of his recorded versions of the songs of Tagore, such as ‘Na Chahile Jare Pawa Jay’, ‘Srabonero Gogonero Gaay’, still showcase one of the many dimensions of Manna Dey as a versatile genius. Later, he would sing some of the songs of Tagore translated into Hindi. The project, though reached a great commercial success, might not have really been liked by Manna Dey, as he would emphasize more on the originality of the songs. It is known to many, during his last days, Manna Dey would be obsessed with his passion to sing the songs of Tagore.

Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would be actively involved with many leftist organizations during his college days. His inclination towards leftism would further be exposed when he would be noticed to be connected with the Indian People’s Theater Association (IPTA) and would be introduced to Salil Chowdhury, an association which would be resourceful for the development of Indian music. The IPTA, one of the major grounds of establishment of it being the Bengal famine of 1943 and the inaction of British administration and wealthy Indians to prevent it, would bring them together and serve the country with many a patriotic songs that would rightfully project both of them as strong patriots. In the year of independence, in 1947, when Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would just be a twenty-seven old man, he recorded the song, ‘Gnayer Badhu’ that was both written and tuned by Salil Chowdhury. The much unconventionally structured six minute long song, recorded on the two sides of a 78 rpm disc, depicted the life of a rural bride that might get destroyed by the famine. Having reached the greatest height of success, the duo of Salil Chowdhury and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would then create unparalleled melodies upon the poems of Sukanta Bhattacharya, a noted communist activist of the time, such as ‘Abak Prithibi’ and ‘Runner’, and the one by Satyendranath Dutta, ‘Palkir Gaan’, Salil Chowdhury tuning them up and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay eventually singing them for the public.

Most surprisingly, the closest contemporary of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, Manna Dey would be first introduced to Salil Chowdhury when the latter would migrate to Bombay in the year, 1953, as the music director to the film, ‘Do Bigha Zamin’, that was to be directed by Bimal Ray. Manna Dey himself has said, he was quite impressed with the blend of the convention of the folk melodies of the East and the melodies of the West that Salil Chowdhury applied to the songs, ‘Dharti Kahe Pukar Ke’ and ‘Hariyala Sawan Dhol Bajata Aaya’, in the film mentioned above. Patriotism would not cease to obsess Salil Chowdhury even when he was Bombay in the post-independence era, the song, ‘Aye Mere Pyare Watan’, in the film, ‘Kabuliwala’, reflecting a great concern for the country that he as well as Manna Dey possessed. Manna Dey’s association could be further emphasized upon in the context of his songs, ‘Dhonno Ami Jonmechhi Ma’, ‘Manbo Na E Bondhone’, ‘O Alor Pothojatree’ and ‘Aowan Shono Aowan’ that Salil Chaudhuri tuned when both of them were a part of the IPTA, Bombay, sometime around the 1970s. Manna Dey, also a twenty-seven year old man when the country got her independence, would later record some patriotic songs in Bengali, such as, ‘Bharat Amar Bharatbarsha’ or ‘Tabo Charana Nimne’, the latter for the film, ‘Subhash Chandra’.

Manna Dey, though not much actively involved in politics, would otherwise be influenced by the concept of love interests in adolescence, particularly for college-goers. Such natural infatuations for a student towards his female friends would be well expressed in his songs, such as, ‘O Keno Eto Sundori Holo’, ‘Sundori Go Dohai Dohai’ or ‘Lal Mehedir Noksha Haate’ that he sing with so much adeptness that they would echo and reflect the sentiments of many young people all across Bengal. Even before Manna Dey sang these songs, romanticism would be expressed in Bengali songs but not in such a universal manner but in quite a grossly melodramatic way. The songs are relevant even to this date when so much of romance is predominant in the songs of Bengal still not matching up to the height of the ones Manna Dey sang.

Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would always have a fair contrast between their ways of execution of the songs they would sing. Manna Dey hailing from a background of classical music would have a viewpoint of improvisations often tending towards an even more modernistic approach while singing the song, though his method would remain quite traditional. Even during the sessions when a song was to be recorded, Manna Dey would prefer some practicing prior to the taking. In his live concerts, he would often improvise on the spot and come up with new avenues especially for the songs that accord to the Indian classical melodies. Manna Dey, having been perfectly educated in Indian classical music, would sing his songs in his live concerts with impromptu improvisations. The numbers adapted from the popular classical compositions of India would be filled with an altogether significant individuality. Though he himself learned Indian classical music to the fullest extent and would quite consciously avoid the trend of the hollow classicism all the celebrated Indian classical musicians of the time would bear within themselves, still, he would certainly be thoughtful about his background and would keep quite close to the knowledge he had acquired only as much as he would want to; the songs that he would sing would have clear reflections of such an insight he would possess. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, on the other hand, would comfortably accept spontaneity instead of a practiced expertise that is suggested by the tradition of the classical arts. He has said, he did not train under any Indian classical master except for the initial years of his life when he would take some lessons from Phanibhushan Bannerjee, a student of Ustad Faiyaz Khan; and, he seemed not to be much perturbed with it. It is also known from his interviews aired on the television, he believed, the excess exercises prescribed by the experts of Indian classical music of the time, would have taken serious tolls on his voice, a fact that emphasizes the belief, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay had beaten the others through his voice which he always treasured.

Even though Hemanta Mukhopadhyay is denied of the knowledge of Indian classical music, it is always surprising as to how he would tune his songs into melodies that accorded to the ones of above tradition. Songs such as, ‘Muchhe Jawa Dinguli’, a perfect composition in the raga, Parameshwari; ‘Woh Shaam Kuchh Ajeeb Thi’, an exemplary parallel to any composition in the raga, Kalyan; or, ‘Jhar Uthechhe Baul Batash’, a composition close to the raga, Bageshree; proclaim the somewhat strong authority that Hemanta Mukhopadhyay had held upon the disciplines of Indian classical melodies. Some of his compositions even came out from some instant information that he would gain in the moment. Pulak Bandyopadhyay, the one who wrote maximum of Manna Dey’s songs once visited the residence of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay for the work for the film ‘Raag Anuraag’. He spent the previous day with Manna Dey, when he saw Manna Dey was practicing the Indian raga, Patdeep referring to many classics set to the raga. The next day, Bandyopadhyay proposed to Hemanta Mukhopadhyay that he tune a song from the film into the raga, Patdeep. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, who knew about Manna Dey’s inclination towards classicism could plainly assume, Bandyopadhyay had spent some time with Manna Dey. However, appreciating the fact that Bandyopadhyay was moved by the raga, he composed the song, ‘Sei Duti Chokh’ with a perfect application of the raga.

The genius of Manna Dey would surely be acknowledged by Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, so much so, that Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would send his daughter, Ranu Mukhopadhyay to Manna Dey for her training in music. In the context of the relationship between the two, Haimanti Shukla, a junior contemporary of both of them, recalls, “Once Manna Dey performed for two and a half hours. The next day when I went to see Hemanta Mukhopadhyay at his residence, I was eventually asked about the concert of Manna Dey, the previous day. Upon hearing me mention, he sang for two and a half hours, he said, ‘You must say, he sang for five hours’, referring to the two and half hour practice he would probably have done before getting on to the dais.” In this regard, it must be mentioned, Haimanti Shukla sang the song, ‘Amar Bolar Kichhu Chhilo Na’ that was tuned by Manna Dey, during the initial years of her career. It was when the time came for Manna Dey to sing the songs tuned by Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, their friendship and fondness towards one another grew even more. Among the popular numbers sung by Manna Dey, the ones such as, ‘O Kokila’, ‘Ogo Chandrabadani’ and ‘Jago Notun Probhaat’ were tuned by his closest contemporary, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay. Being the music director, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay was sure to take the best of the best of Manna Dey. As it has been mentioned earlier with adequate justification to Manna Dey’s compartmentalization of traditionalism and modernism in his approach to recording a song, in parallel ways, a strong perfectionist, he would consume a lot of time while recording a song at the studio, practicing in the beginning, taking the song for many times and finally choosing the best among the cuts taken; whereas Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would prefer the song to be taken in a fresh voice. In this context, Durbadal Chattopadhyay, the veteran violinist comments, ‘Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would avoid the over exercising and excess rehearsals for a song prior to taking it. He believed more on the spontaneity of his fellow musicians. Manna Dey, on the other hand would always tend to more and more perfection rehearsing the song over and over again.’ Once it so happened, Manna Dey went to the studio to record a song that was tuned by Hemanta Mukhopadhyay and started rehearsing. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, on the other hand, instructed the recordist to keep only the first cut taken and eventually left the studio. However having taken numerous cuts, when Manna Dey started choosing the best among them, he found the first one to be the best. Later when he was informed of the game played by Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, he was surprised to realize their understanding afresh. The song, ‘Jonomo Obodhi Kaar’, that he tuned for the film, ‘Dadar Kirti’, was sung by Manna Dey, would be a perfect blend of literally all the genres of Indian music ranging from the tradition of Keertana to the one of Dhrupad. Being the music director to any film, he would adequately use Rabindrasangeet there too. The film was directed by Tarun Majumder with whom Hemanta Mukhopadhyay shared a great association ever since 1962 when Majumder first approached him to score the soundtrack for his film, ‘Palatak’.

Manna Dey would compose songs but not as frequently as Hemanta Mukhopadhyay. During his days as an assistant to his uncle, he would tune up songs for experimentation. Later, when he would seriously struggle for his existence in Bombay, he would be offered movies with relatively low budget. Once he would start singing songs in Bengali, it can be observed, most of the songs he sang were tuned by him. He has also mentioned the fact, the first songs he tuned were, ‘Ogo Sarati Jamini Jagi’ and ‘Baluka Belay Alash Khelay’, out of which the first one was to be sung by K.L. Saigal; he couldn’t finally sing it and Manna Dey himself recorded the song in his later years. The second one was recorded by Supriti Ghosh. It was actually when Lata Mangeshkar would cancel her dates for recording two songs, ‘Kotodure Ar Niye Jabe Bolo’ and ‘Hay Hay Go Raat Jay Go’, that Manna Dey had tuned for her, Manna Dey himself decided to record the songs and publish. Ever since the popularity of the songs, Manna Dey would explore the genre of basic songs in Bengali with utmost confidence. Many of the songs, as has been said earlier, would be tuned by him, some of them being close to the Indian ragas. Songs such as ‘Sundori Go Dohai Dohai’, the one set to the raga, Yaman or ‘E To Raag Noy’, to the raga, Durga would present his sound knowledge on the conventions of Indian Classical music, over exercising of which leading to narrow-mindedness, would always be criticized by him. The film, ‘Shesh Prishthay Dekhun’, would feature Manna Dey as the music director who would sing in the film a duet with Hemanta Mukhopadhyay his own composition, the song, ‘Satyameva Jayate’.

The ever astounding confluence of Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay could be observed in both Bombay and Calcutta. During the days of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay in Bombay as Hemant Kumar, the film, ‘Narsi Bhagat’, that released in 1957, would feature an incredible trio of Manna Dey, Hemant Kumar and Sudha Malhotra singing the song, ‘Darshan Do Ghanashyam’ that was tuned by Ravi, the celebrated music director of Bombay who started his career as an assistant to Hemant Kumar when he was working for the film, ‘Samrat’. Manna Dey and Hemant Kumar would again work together for the film, ‘Biwi Aur Makaan’ that was directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee and was released in 1966. The songs where Manna Dey and Hemant Kumar would both work together are ‘Jab Dosti Hoti Hai’ and ‘Aa Tha Jab Janam Liya Tha’, where, in the former, it would be observed, the song would be tuned in accordance with the convention of the folk melodies of Punjab with a perfect application of the Dholak, and in the latter, it is clearly noticeable that Hemant Kumar harnessed the talents of all the other singers involved into the song apart from Manna Dey and Hemant Kumar himself. The others who joined in the first song were Ghulam Mohammed and Balbir Singh, and the one to join in the second song was Mukesh. The title song of the film, ‘Khul Sim Sim Khullam Khulla’ that was sung by Manna Dey and Bula Gupta would just an extraordinary musical masterpiece, though the tune was a repetition of ‘Shing Nei Tobu Naam Taar Singha’, a classic number by Kishore Kumar from the film, ‘Lukochuri’, that was released in 1957 once again featuring Hemanta Mukhopadhyay as the music director.

In Calcutta, the films ‘Stree’ in 1972, ‘Shesh Prishthay Dekhun’ in 1973, ‘Sannyasi Raja’ in 1975, ‘Bhola Moira’ in 1977 and ‘Lalan Fakir’ in 1987. ‘Stree’ starring Uttam Kumar and Soumitra Chattopadhyay featured Manna Dey to sing for the former and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay for the latter; the film comprised of two musical duets by Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, ‘Hajar Taka r Jharbati Ta’ and ‘Sakhi Kalo Amar Bhalo Lagena’ where, apart from the individuality they would possess, their expertise were exhibited holistically as something out of the world. The music director of the film, Nachiketa Ghosh would eventually succeed in applying the two great voices in yet another film, ‘Sannyasi Raja’, starring Uttam Kumar. Veteran master of the Sitar, Pandit Shyamal Chattopadhyay, a close friend to Ghosh recalls, “He was one of my closest friends. One fine evening, he came over to my place, took out the Harmonium and started humming. However, one by one, all the songs of the film, ‘Sannyasi Raja’ were successfully tuned.” The plot of the story revolving around the popular incident of the Bhawal case, exploited the vivacity of Uttam Kumar to the level of his projecting the two opposite sides of the characters he played. Ghosh’s wisdom and adeptness at applying the appropriate voice for the appropriate man on the screen might be doubted, but in this regard, it must be looked into the voracious change of the character played by Uttam Kumar from an influential king to a saint has been paralleled by the voice of Manna Dey in his former form and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay in the latter. The energized attitude of the king has been perfectly matched by the rigorous confidence of Manna Dey in his songs, ‘Kaharba Noy Dadra Bajao’ or ‘Bhalobashar Aagun Jwalao’, the confidence being achieved through his inclination towards classicism, whereas, the simplicity of the saint has been corresponded with the minimalistic vocal exercise of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay in his song, ‘Ka Tobo Kanta’. In this regard, Suparna Kanti Ghosh, who appeared earlier in the discourse, would recall, ‘During the days the songs of ‘Sannyasi Raja’ were being recorded, we used to stay in Nataraj Hotel in Bombay. One afternoon, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay arrived there and asked my father to tune up a song for him to sing in Sannyasi Raja, all the other songs being sung by Manna Dey. My father would ask him for a date once he would be back to Calcutta and would finally record ‘Ka Tobo Kanta’, the song that was as sensational as any other songs of the film.”

With the fair reference to Uttam Kumar, their cordiality could be seen to find a new avenue to be explored when both of their gestures exemplified a mutual respect. Once, Anil Bagchi, the music director of the film, ‘Anthony Firinghee’, starring Uttam Kumar, approached Hemanta Mukhopadhyay with the songs of the film. It is generally believed, he composed the songs majorly for Manna Dey he composed the songs, but somehow complying with some internal disputes raised by the producer, Bagchi had to come up to Hemanta Mukhopadhyay. The producer was eventually contacted by Hemanta Mukhopadhyay and convinced of the fact, the songs would befit the voice of Manna Dey the most. Even a century later, people discuss about the film being the perfect projection of the pair of Manna Dey and Uttam Kumar. It would be often mentioned by Manna Dey in his interviews, once Manna Dey was driving down the streets of Bombay when he suddenly saw Uttam Kumar crossing the road. Uttam Kumar happened to be in Bombay as he was busy producing his film, ‘Chhoti Si Mulaqat’, there. Manna Dey stopped the car and summoned Uttam Kumar near him just to see him carry a tape recorder with him. Upon being asked, he replied that he was carrying the songs for ‘Anthony Firinghee’ with him just to get accustomed with the style of Manna Dey before embarking into lip-syncing them in the film. The pair of Manna Dey and Uttam Kumar, the former singing in background for the latter on screen first introduced by the film, ‘Sankhabela’, reached the pinnacle of success through the film ‘Anthony Firinghee’.

Much after the success of the film, ‘Anthony Firinghee’, the film, ‘Bhola Moira’ was made on the life of Bhola Moira himself; once again Uttam Kumar playing it on the celluloid; who was known for his rivalry with his contemporary Anthony Firinghee; where again, it could be seen, Manna Dey sings for Bhola Moira and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay singing for Anthony Firinghee on screen. The song, ‘Ki Holo Ki Holo Radhar’ portraying the musical fight within Anthony Firinghee and Bhola Moira in the film must be considered as an exemplary resource to the mutual admiration of Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay towards one another.

The film, ‘Lalan Fakir’, comprises of a marvelous song, ‘Chirodin Kacha Basher Khacha Thake Na’ which is again a duet of Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay. The first half of the song has been sung by Manna Dey who clearly projects the pathos of the song through the modulations of his voice, whereas, the second half features the bold voice of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay that seems to have justified the questions of fragility put forth by the previous part of the song.

Soumitra Chattopadhyay, another of the superstars from film industry of Bengal, too had sung many songs on the screen where both Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay had lent their voices. Apparently mettlesome in attitude on screen, the superb modulations in the voice of Soumitra Chattopadhyay would appropriately be matched by the mellifluous voice of Manna Dey. The film, ‘Tin Bhubaner Pare’ and the film, ‘Basanta Bilap’, featured songs such as, ‘Jibone Ki Pabo Na’ and ‘Aagun Legechhe Aagun’ respectively, exploited the convergence of the voices of Soumitra Chattopadhyay and Manna Dey to the greatest level. The song, ‘Hoyto Tomari Jonno’, from the film, ‘Tin Bhubaner Pare’, would project an opposite dynamicity to the song, ‘Jibone Ki Pabo Na’, with perfect juxtaposition of the an incredible blend of the gestures of Soumitra Chattopadhyay on screen and Manna Dey singing for him. Hemanta Mukhopadhyay too sang for Soumitra Chattopadhyay on screen, some of the most popular exemplars of the duo being, ‘Eki Choncholota Jage Amar Mone’ from the film, ‘Atal Jaler Aowan’ and ‘O Akash Shona Shona’ from the film, ‘Ajana Shapath’. It would still be believed, the voice of Manna Dey, rather than Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, would match more with the voice of Soumitra Chattopadhyay on screen for Manna Dey would not possess a baritone as Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, the same being missing in the voice of Soumitra Chattopadhyay in his earlier days. Soumitra Chattopadhyay would be respectful towards both Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay and often cherish his times with them, saying, “I would precisely not have liked if ‘Hoyto Tomari Jonno’ would not be sung by Manna Dey or ‘O Akash Shona Shona’ would not be sung by Hemanta Mukhopadhyay.”

Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay shared quite a nice and fair attachment with one another. Haimanti Shukla once again recalls, “They had the perfect friendship, both of them remaining aware of each other’s performances.” The works they have done together have always gone on exemplifying the fact, true geniuses never cease to exist and of course both of their popularity denied the old notion of two kings ruling one kingdom. The century that has been quite significantly enlightened by the works of the two continues to be the most important one for not only featuring many musical masterpieces but also witnessing some of the greatest correlations in the field of music. The most extraordinary of all their positive contributions to the songs in Bengali is that they never compromised with the pronunciation of the words. Srikanto Acharya, the young singer of today who started his career singing the songs of the legends, comments, “Both Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay emphasized upon making their pronunciation perfect. Apart from that, the way they controlled their breath and sang is still admirable. I may not have got the opportunity learn from them directly, I still learn from whatever I can gather from their records.” Dr. Rajat Subhro Banerjee, the one who learnt directly from Manna Dey has also said how Manna Dey would focus on making the pronunciation perfect. “When I went to learn from him, the first thing that he told me was that I must make the pronunciations clear,” said Dr. Banerjee. Bengal still misses the voices of Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay even after both of them left the world, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay in 1989 and Manna Dey most recently in 2013. It would be most appropriate to conclude with the comment of Maestro Bickram Ghosh, one of the most acclaimed musicians practicing Indian classical music and the art of fusion as well as scoring films: “I certainly miss the voices of Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay. Of course, we have great talents in our times, but working with them would have been something beyond an honor”. His statement revivifies the fact, the relevance of Manna Dey and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay is quite prominent and the legacy which they have created through their works of lifetime shall live on for many centuries to come.

I finally end the discourse acknowledging Pandit Shyamal Chattopadhyay, Srikanto Acharya, Durbadal Chattopadhyay, Suparna Kanti Ghosh and Haimanti Shukla who all have provided me with the necessary facts that could be included in the article. I thank Dibyayan Banerjee who helped me procure the autobiography of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay that was out of print for long. I thank Pandit Anindya Banerjee for making arrangements for my interviewing Soumitra Chattopadhyay. I particularly thank Dr. Rajat Banerjee and Saptarshi Bhattacharya who have provided me with several minute details from which selected anecdotes could be referred to for the development of this article. At the end, I thank my Guru, Maestro Bickram Ghosh who helped me for an extensively comprehensive study of the works of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay as a music director to films.

Bibliography:

- Saha, Bijesh (ed.), Masik Krittibas, Vol. 6, May 2019, pp. 7-10

- Chattopadhyay, Anindya (ed.), Pratidin (ROBBAR special issue), November 2017, pp. 4-27

- Bhattacharya, Sankarlal, HEMANTAKE NIYE, Kolkata: Sumitra Prakashani, January 2020

- Chakrabarty, Manas, (ed.), MANNA DEY, Kolkata: Srishti Prakashan, 2000

- Dey, Manna, AMI NIRALAY BOSHE, Kolkata: A. Mukherjee and Co. Pvt. Ltd., 1997

- Dey, Manna, JIBONER JOLSAGHORE, Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2017

- Mukhopadhyay, Hemanta, ANANDADHARA, Kolkata: New Bengal Press Pvt. Ltd. 1988

Internet Sources:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mZPxxIPects&t=1856s

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_-dUGb8Yq8

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kXBx_UVFDZ4

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3UnfwlVRHMo&t=1335s

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sK_A2W6KiQU&t=303s

- https://www.anandabazar.com/supplementary/patrika/hemantayan-a-tribute-to-veteran-singer-musician-hemanta-mukhopadhyay-from-sarbani-1.162066

- https://www.anandabazar.com/entertainment/a-tribute-to-celebrate-100th-birth-anniversary-of-singer-hemanta-mukherjee-dgtl-1.1019322

- https://www.anandabazar.com/editorial/special-article-about-hemanta-mukherjee-1.1005797

- https://www.anandabazar.com/supplementary/patrika/music-director-shantanu-bose-memorises-singer-manna-dey-1.137925

- https://www.anandabazar.com/entertainment/a-special-write-up-on-manna-dey-s-birth-anniversary-dgtl-1.794968

- https://www.anandabazar.com/photogallery/entertainment/old-frame-of-manna-dey-s-in-his-birthday-dgtl-1.794959

- https://www.anandabazar.com/supplementary/anandaplus/manna-dey-appeared-as-a-musician-first-then-he-is-a-singer-1.218766

- https://www.anandabazar.com/manna/manna-dey-exclusive-in-ananda-plus-web-edition-1.209182

- https://www.anandabazar.com/manna/manna-dey-was-the-master-of-the-celeb-singers-sons-1.183171

SUBHADRAKALYAN